The early church in Urquhart, the Aird and Strathglass

This blog is more or less a transcript of a talk I gave last weekend at the Highland Archaeology Festival in Inverness.

It was a great conference and it was wonderful to meet so many people in person! Thanks very much to Grace from Highland Historic Environment Record for inviting me to speak.

The talk wasn’t recorded, so I’m publishing it here. These are still-developing thoughts, related to my ongoing research into bishop Curetán of Ross, who was the subject of my recent Groam House Lecture (still available to view for £3/£6).

If anyone has any comments or feedback, I’d love to hear them.

(Footnotes are in the slides.)

My PhD research methods

I’ve just finished my first year of PhD research at the University of Glasgow, where I’ve been focusing on the early church in the Moray Firthlands between around 650 and 800 AD.

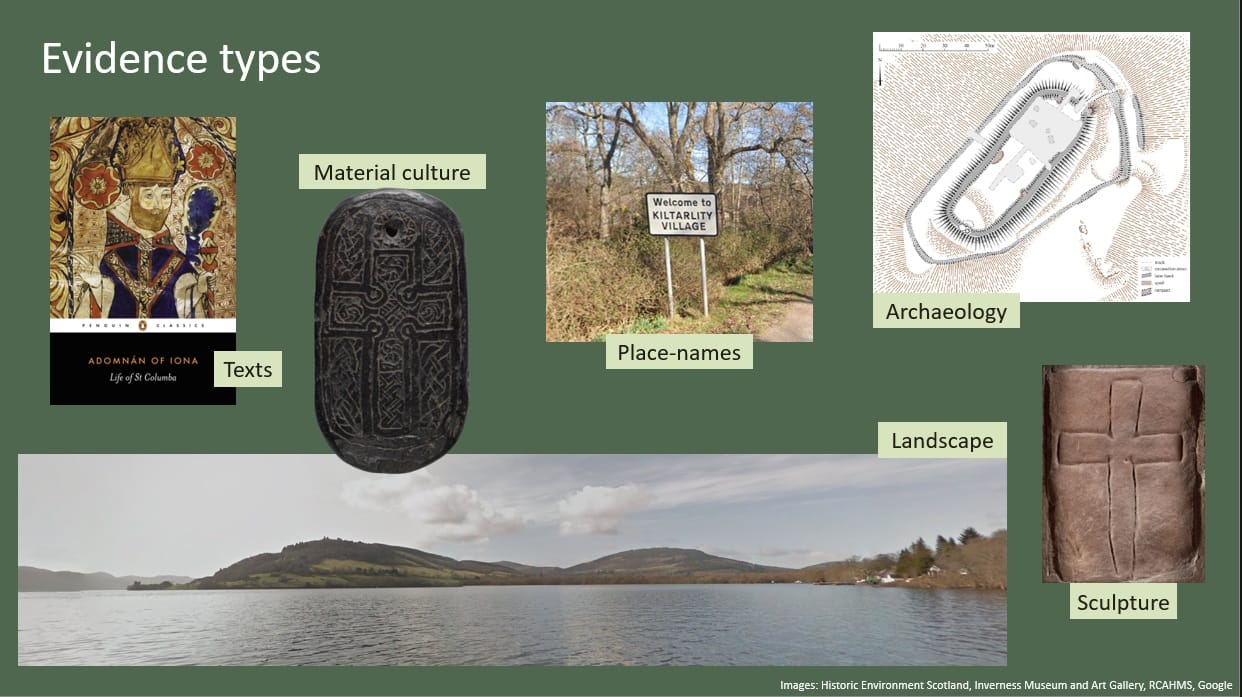

There’s almost no written evidence for the later first millennium, so my method involves combining the tiny scraps of textual evidence that we do have with evidence from other sources—place-names, sculpture, archaeology, material culture and the landscape itself.

I want to talk about how I’m combining those sources to try to shed more light on the early church in the part of Inverness-shire west of the River Ness and Loch Ness, comprising the Aird, Urquhart and Strathglass.

I’ll be talking about the pastoral, rather than monastic church. Unlike the early medieval monastic sites that we know about in this region, at Portmahomack, Rosemarkie and Kinneddar, I'm looking at churches provided for the lay Christian population, which would have been overseen by a bishop.

Columba's miracles in Inverness-shire

My starting point is the Life of St Columba, written by Adomnán, the ninth abbot of Iona, around the turn of the eighth century. This is our only contemporary textual source for early medieval Inverness-shire, so it’s worth mining for as much information as possible.

It’s not a biography, but rather a collection of anecdotes about the miracles worked by Columba, who founded the monastery of Iona in 563 and died in 597.

Several of those miracles take place in Inverness-shire, including, most famously, Columba’s encounter with a water-beast in the River Ness, often held up as the first documented sighting of Nessie.

What’s unusual about that episode, and several others that I’ll look at in a moment, is that Adomnán specifically names and describes the places where these miracles occur. I want to think about what his decision to show Columba in those specific places might tell us about the church in the area at the time Adomnán was writing.

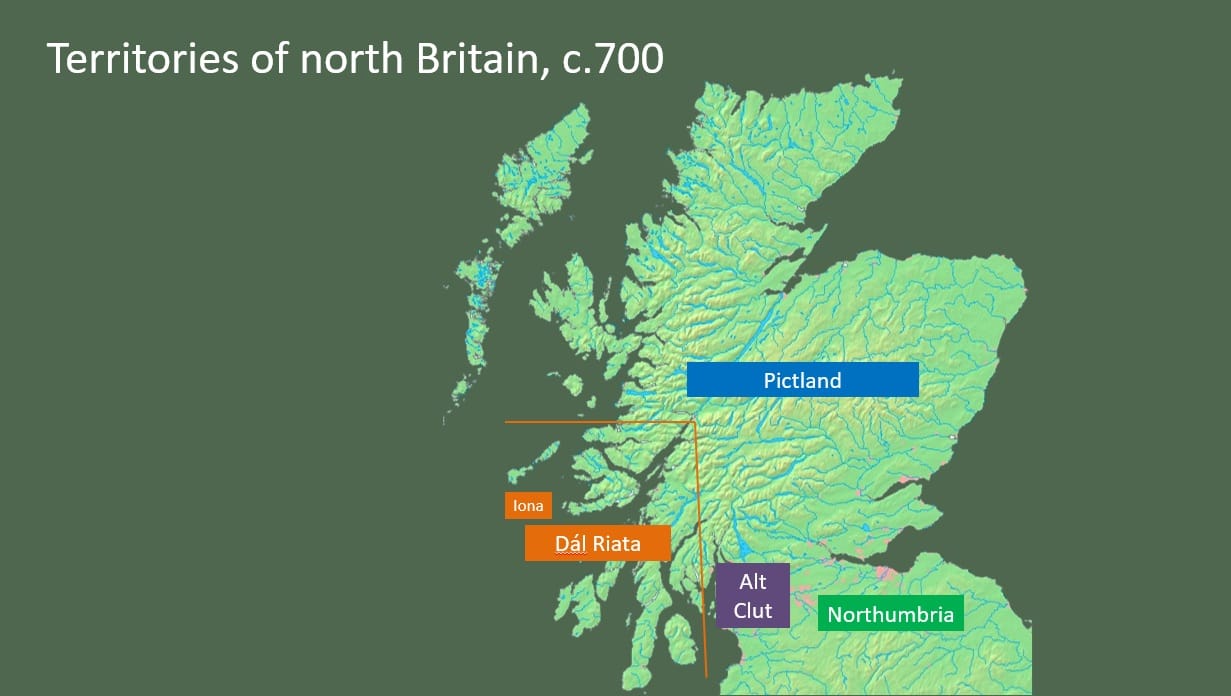

Territories of north Britain, c.700 AD

First, a bit of context. In both Columba’s and Adomnán’s time, the Firthlands are in Pictland, which is foreign territory to the monks of Iona. Their monastery is in the Gaelic-speaking realm of Dál Riata, modern Argyll.

Pictland surrounded Dál Riata to the east and north, stretching from Fife to the Western and Northern Isles. But Adomnán only shows Columba in certain parts of it.

There are nine or ten chapters set in Pictland where Adomnán explicitly names the location. Two are set in Skye. One is set by a loch called stagnum Lochdae, which is usually considered to be Loch Lochy in the Great Glen, although that’s not a totally satisfactory interpretation. The remaining seven are set along Loch Ness and the River Ness.

If we home in on those seven chapters, we see that Adomnán names and describes real places that we know today. I’ll give four examples.

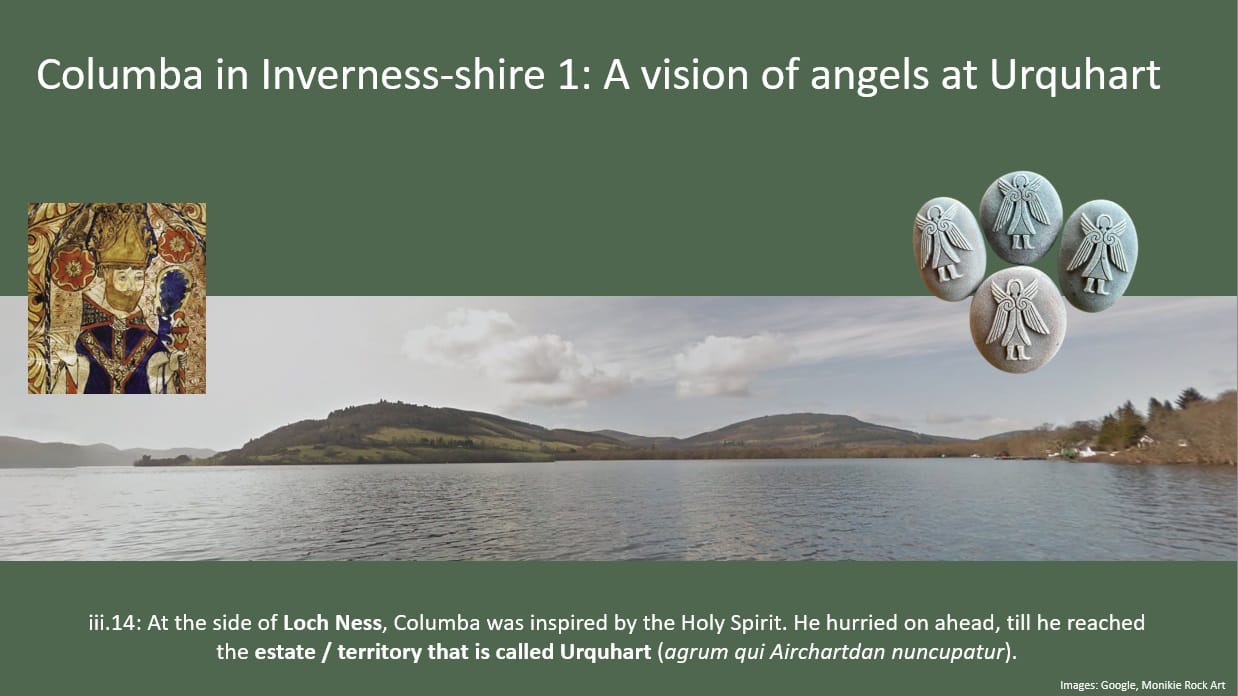

Columba at Urquhart on Loch Ness

First, in Book 3, chapter 14, Columba is travelling beside Loch Ness when he sees a host of angels. He predicts that they’ve come to accompany a pagan to heaven, as the man has been good throughout his whole life. But the man must first be baptised.

Adomnán says that Columba went as fast as he could until he came to ager qui Airchartdan nuncupatur, the estate or territory called Urquhart. There he baptised an old man called Emchath and his whole household. Emchath then ascended into heaven with the angels that came to meet him.

The notable things here are that Loch Ness and Urquhart are specifically mentioned, that Columba sees angels hovering over Urquhart, and that Emchath has a household, implying that he is of elite status.

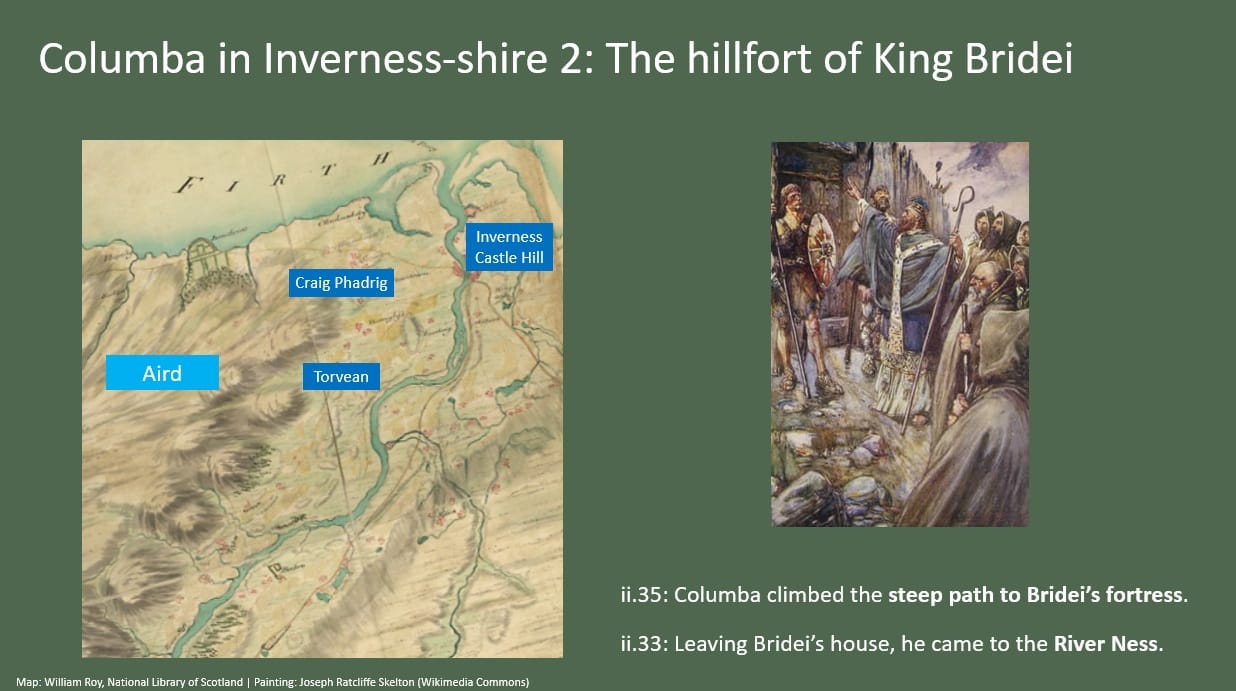

King Bridei and his hillfort by the River Ness

The good Pictish pagan Emchath at Urquhart is strongly contrasted with the Pictish king Bridei, who is mentioned in four chapters. This king is initially rude and hostile to Columba, and he has a court mage, Broichan, who tries to thwart the saint with his pagan magic.

Adomnán tells us that Bridei inhabits a fort that is up a steep path, near the River Ness. The clear implication is that it’s a hillfort, although its exact location has been much debated. Craig Phadrig, Torvean and the Inverness Castle Hill could all fit the description. But what’s important for this talk is that Adomnán specifies that the fort lies on or near the River Ness.

The water-beast in the River Ness

The same applies to the episode with the water-beast. This terrifying creature has just killed a man when Columba arrives at the riverbank, and it tries to kill one of Columba’s monks, Luigne moccu Min, until the saint repels it with his holy power.

This is often held up as the first historical mention of the Loch Ness Monster, but Adomnán is explicit that this murderous beast lives in the River Ness, not the loch.

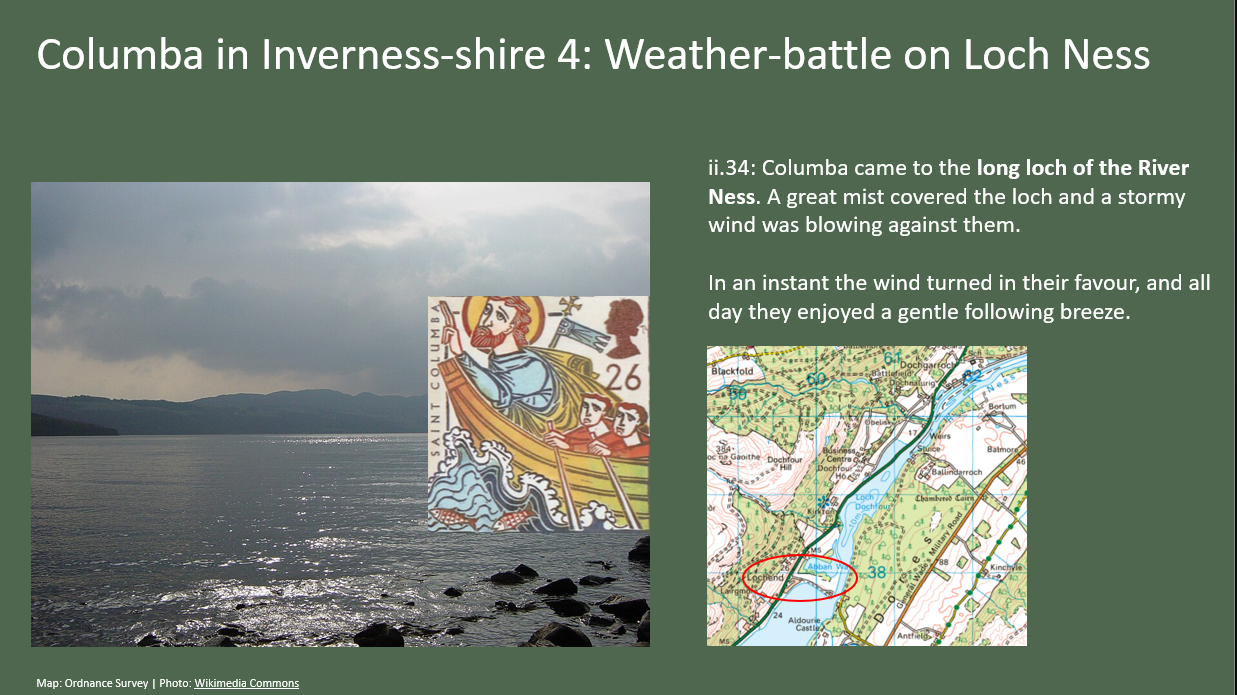

A weather-battle on Loch Ness

Lastly, in Book 2 chapter 34, the mage Broichan boasts that he will summon bad weather to prevent Columba from sailing home down the Great Glen.

Adomnán tells us that ‘on the appointed day... the saint came to the long loch of the River Ness' (meaning Loch Ness). The mages began to exult, because they saw a great mist brought up, and a stormy adverse wind.'

But God shortly intervenes on Columba’s behalf. Adomnán says that Columba ‘ordered the sail to be raised against the wind, and the ship moved with extraordinary speed, sailing against the contrary wind.’

He adds that ‘after a short time, the adverse winds were turned about. Throughout that day, driven by gentle breezes blowing favourably, the blessed man’s boat was carried to the desired harbour.’

This miracle surely takes place at modern Lochend, where the River Ness flows out of Loch Ness. I think it’s significant that Adomnán depicts it as the geographical limit of the power of Broichan and the other mages surrounding King Bridei. We can almost hear them cursing as Columba sails away down the loch and out of their reach.

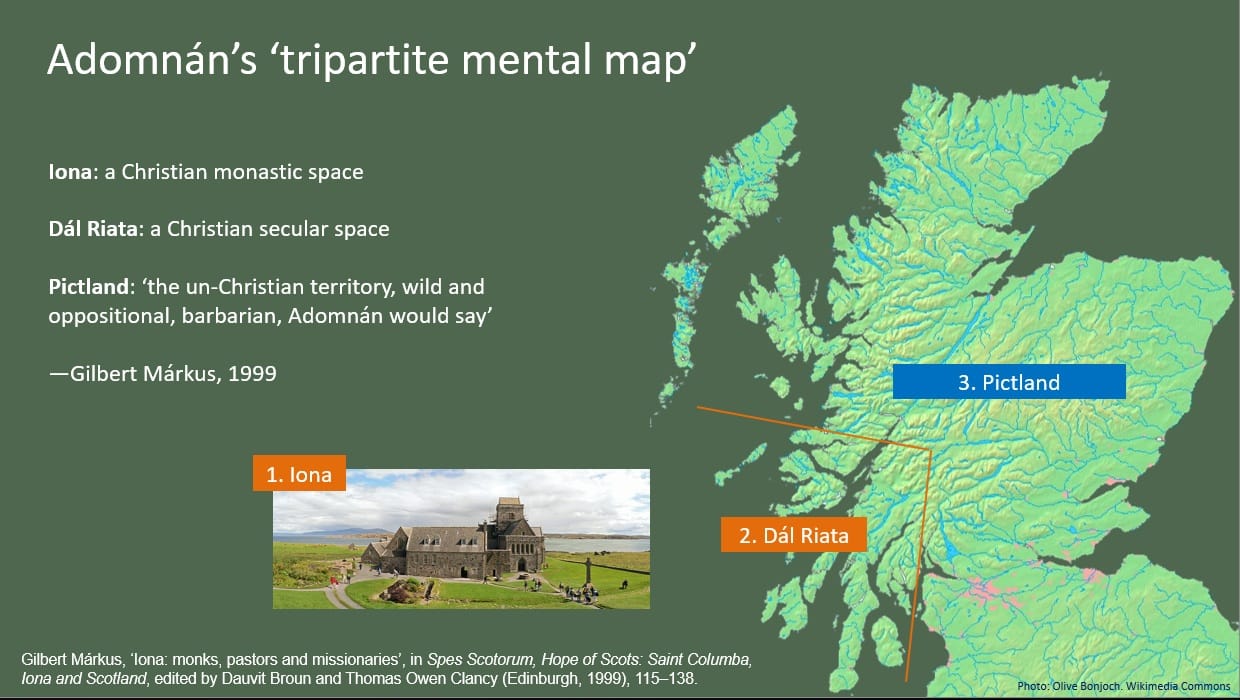

Adomnán's 'tripartite mental map'

This makes me think that when Adomnán explicitly places Columba around the River Ness or Loch Ness, he is making an important distinction.

Gilbert Márkus has written very interestingly about Adomnán having a ‘mental map’ of Iona, Dál Riata and Pictland as three territories with very different characteristics.

In Adomnán’s mind, he says, Iona is a Christian monastic space, and Dál Riata is a Christian secular space. But ‘Pictland represents [the] third region of the mind, the un-Christian territory, wild and oppositional, barbarian [Adomnán] would say.’

But as we’ve seen, there’s some nuance to where these ‘wild, oppositional and barbarian’ things happen. Adomnán shows them happening specifically around and along the River Ness. By contrast, Loch Ness is a place of good Christianised pagans, angelic visions and gentle breezes.

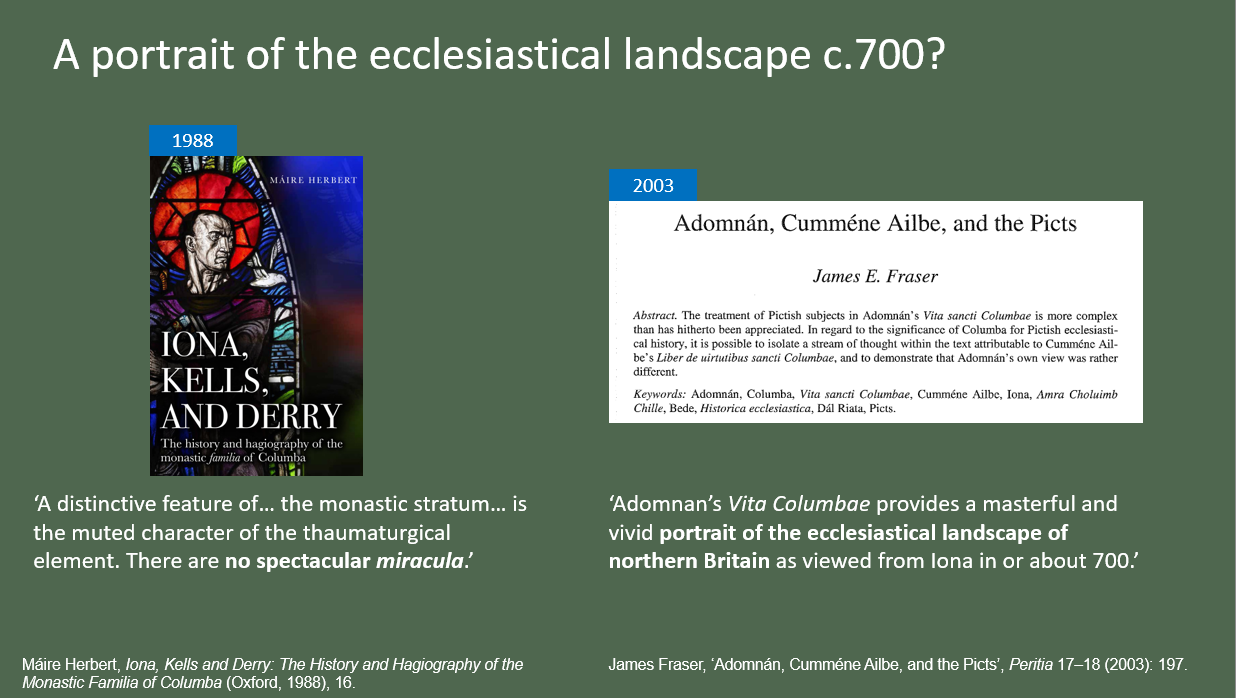

A portrait of the ecclesiastical landscape in Inverness-shire?

So what might Adomnán be trying to tell us? It’s famously difficult to be sure whether he is showing us Columba’s world, in the late sixth century, or his own in the late seventh century.

But with the episodes set in the Firthlands, we may have a slightly better idea. In her excellent 1988 book Iona, Kells, and Derry, Máire Herbert demonstrated that Adomnán copied many of his more mundane stories from a lost Life of Columba, written around 640 by Cumméne, the seventh abbot of Iona.

But she noted that some stories have a markedly more heightened tone, including the dramatic episodes along the River Ness. These did not appear to be borrowed from Cumméne's work.

In 2003, James Fraser built on this idea, and argued that the episodes set in specific places in the Firthlands were written or adapted by Adomnán himself. He proposed that Adomnán was driven by political considerations that made it important to explicitly show Columba at work in northern Pictland.

He concluded that Adomnán was showing us the north in his own time:

Adomnan’s Vita Columbae provides a masterful and vivid portrait of the ecclesiastical landscape of northern Britain as viewed from Iona in or about 700.

And I think there’s another factor that adds weight to this argument.

Adomnán's Law of the Innocents

At the same time as he was writing the Life of Columba, Adomnán was also drawing up a law called the Law of the Innocents, which outlawed violence against women, children and clergy.

He promulgated this law at the Synod of Birr in Ireland in 697, where it was officially endorsed by 91 clerics and kings from Ireland, Dál Riata and Pictland.

One of those clerics was a bishop with an apparently Gaelic name, Curetán, but whose jurisdiction was in Pictland, with its see at Rosemarkie on the Black Isle.

(I'll be using the word 'jurisdiction' because 'diocese' is a contentious word for this period in Britain.)

I think that Adomnán’s specific place-names and accurate descriptions of the Inverness-shire landscape are signs that he visited the Firthlands himself. The timing would be right for a journey up the Great Glen to secure Curetán’s support for the Law of the Innocents.

If that’s correct, it’s possible that we catch a glimpse of Curetán’s episcopal jurisdiction in the Loch Ness and River Ness episodes in the Life of Columba.

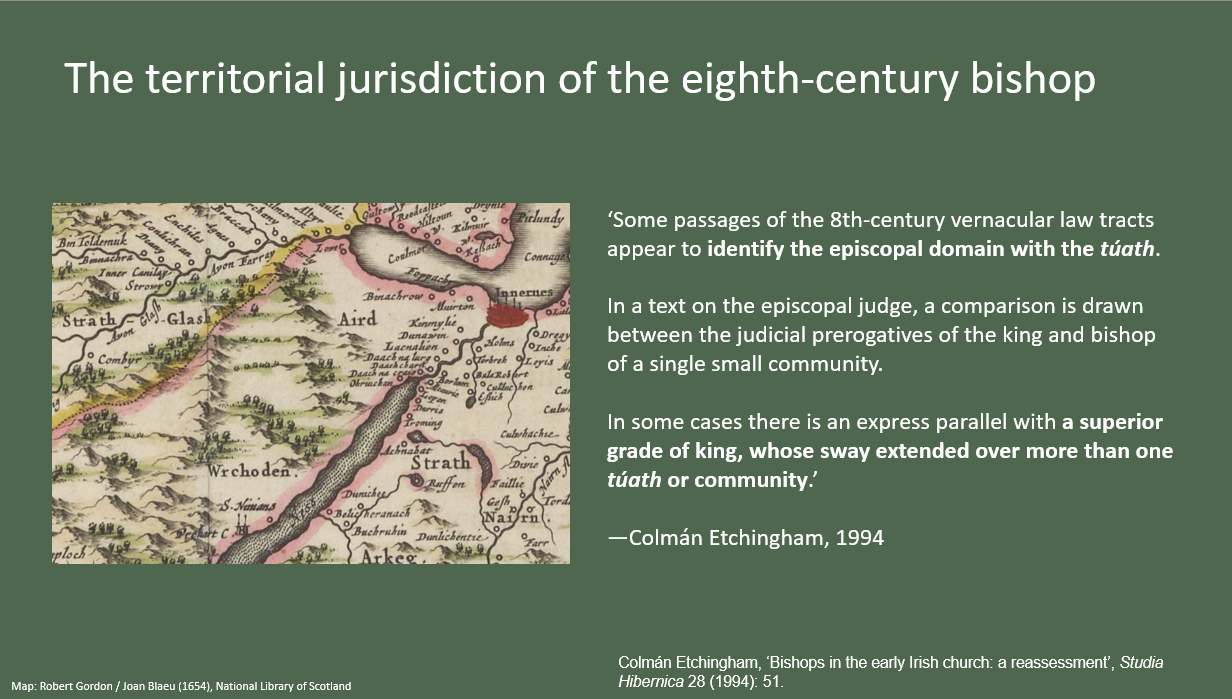

Clues from eighth-century Ireland

We have no direct insight into how a bishop might have operated in Pictland around 700 AD. But some Irish legal texts of the eighth century give some clues.

Colmán Etchingham noted a hint in these texts that Ireland had two grades of bishop: a lower grade who was responsible for pastoral care of the Christian community in a single district, or túath, and a superior grade, who had authority over multiple districts or túatha.

I want to suggest that Curetán equated to a superior-grade bishop, and that in the Life of Columba, Adomnán is showing us two of the districts, or túatha, over which he had authority.

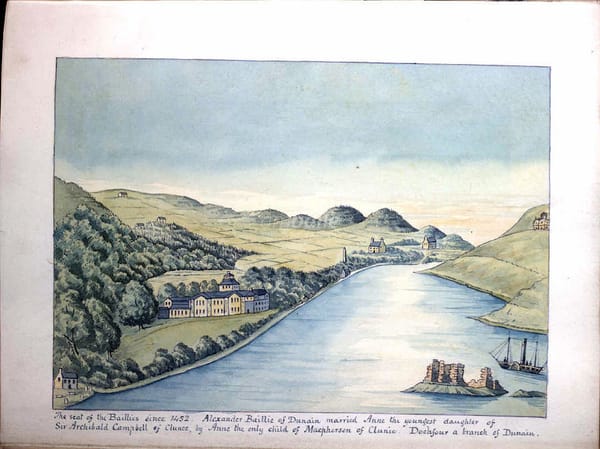

One, of these districts, as Adomnán tells us, was named Urquhart, and I want to suggest that the other occupied the area known as the Aird. The seventeenth-century map below shows the two districts ('Wrchoden' and 'Aird') nicely.

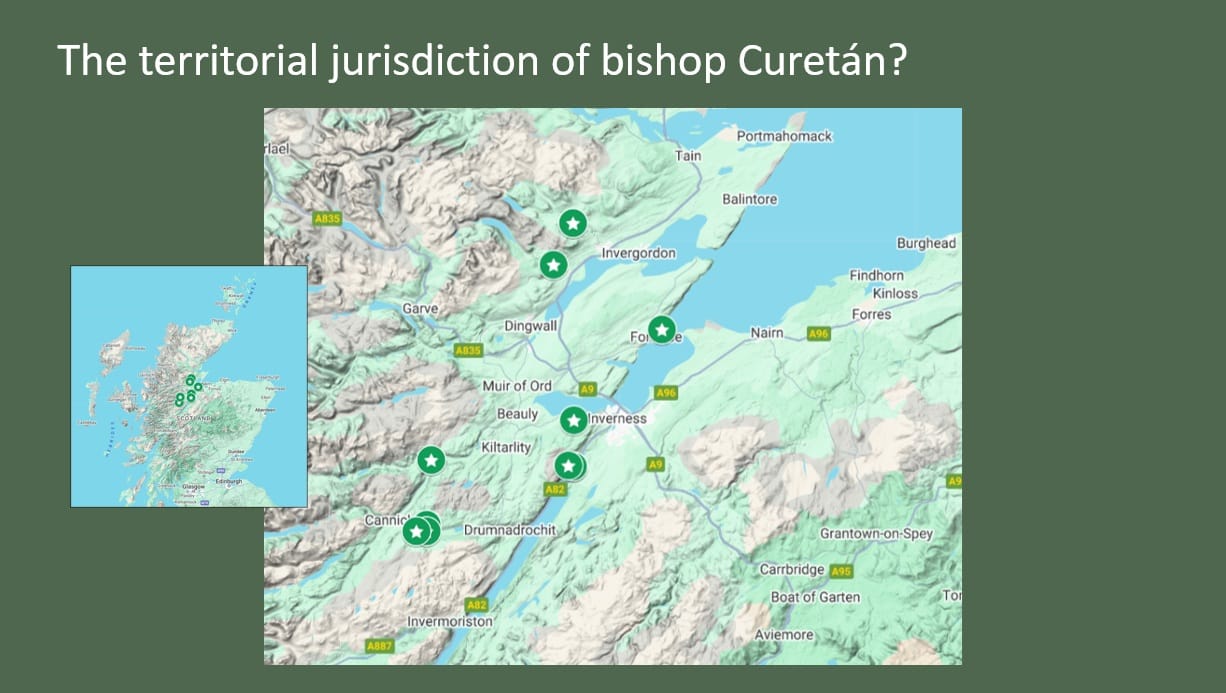

Curetán's episcopal jurisdiction

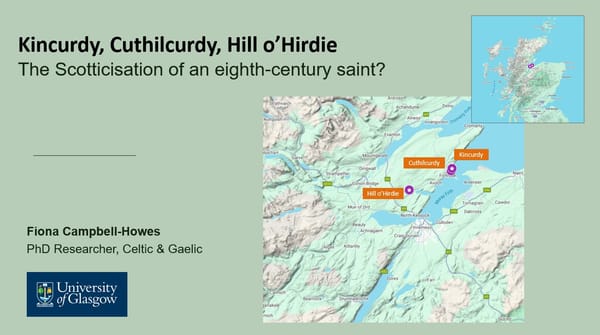

Curetán is usually, and correctly, associated with Easter Ross, and Rosemarkie in particular. But the spread of place-names that include his name (below) suggest that his sphere of influence also extended to the Aird, Urquhart and Strathglass.

There are no dedications to Curetán anywhere else in Scotland (inset map above), which strongly suggests that this distribution reflects his actual jurisdiction.

Evidence for two 7th-century túatha in Inverness-shire

The idea that Adomnán’s Life of Columba is showing us two túatha of Curetán’s jurisdiction receives some support from archaeology, landscape and place-names.

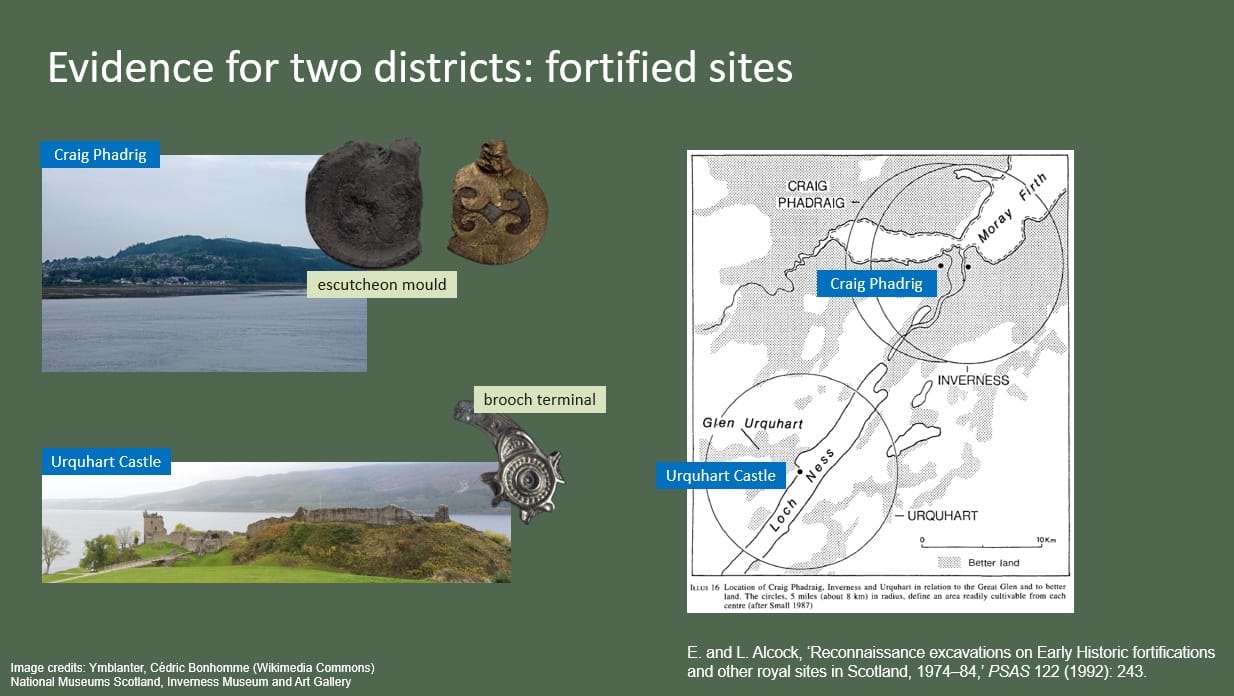

First, both Urquhart and the Aird have a sizeable fort that was occupied in the early Middle Ages. Elizabeth and Leslie Alcock excavated at Urquhart Castle in 1983, and found evidence of an elite stronghold that was occupied from the late sixth century to the ninth. An earlier find at Urquhart of the terminal of a silver penannular brooch reinforces this interpretation.

They were reluctant to characterise it as a royal fort, given its apparent proximity to the fort of king Bridei on the River Ness. But they did see it as the political centre of a territory corresponding to Glen Urquhart and its hinterland.

(Ignore the circles on the map above, which relate to cultivable land.)

Of the three candidate sites for Bridei’s fort, only Craig Phadrig has been excavated, most notably by Alan Small in 1971 and 1972.

This dig was never fully written up, but it did yield evidence of elite early medieval re-occupation in the form of E-ware sherds and a mould for a hanging bowl escutcheon.

So even if Craig Phadrig wasn’t the fort of the historical King Bridei, who died in 584, it could still have been a high-status site in Adomnán and Curetán’s time, a century later.

(I'm tempted to place the historical Bridei's fort on the Inverness Castle Hill, but that's for another time.)

That means we can envisage potentates in residence at both Craig Phadrig and Urquhart Castle in the late seventh century, with one being ruler of the Aird, and the other ruler of Urquhart.

An early church at Temple on Loch Ness?

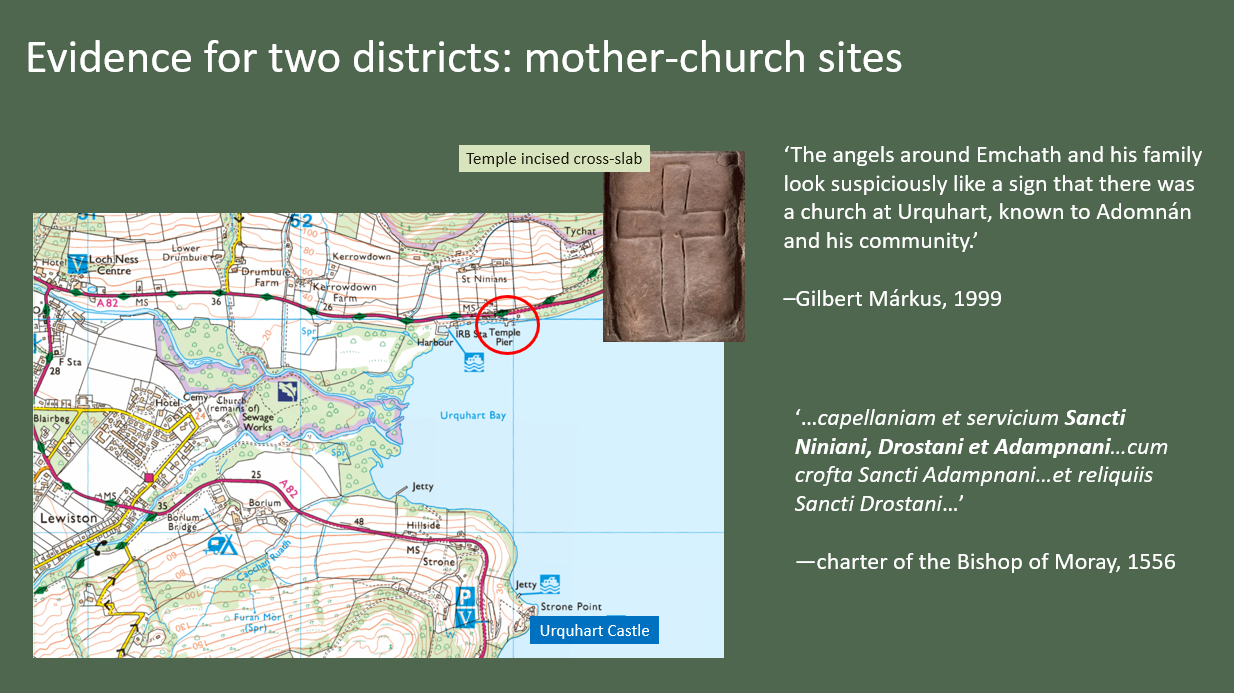

Next, Gilbert Márkus has argued that visions of angels in the Life of Columba and in other early medieval saints’ lives signal the location of a church.

The whole of Book 3 of the Life of Columba is dedicated to angelic visions, but only one occurs in Pictland—the vision that Columba experiences at Urquhart.

The setting of the lost church of St Ninian’s at Temple (circled below), intervisible across Urquhart Bay with the Castle, makes it a good location for a church patronised by a potentate living at the castle site.

This is also suggested by other evidence. An incised cross-slab from Temple is impossible to date, but is consistent with the presence of an early church.

There are also mentions in sixteenth-century charters of chaplainries of Ninian, Drostan and Adomnán at Temple. The Ninian dedication likely dates to the twelfth century or later, but the dedications to Adomnán and Drostan may be early.

The dedication to Adomnán is interesting. Another reason to think that we see the Firthlands of Adomnán’s time in the Life of Columba is that there’s very little evidence of an early cult of Columba in Urquhart or the Aird.

There’s no time to discuss it here, but the tiny hints we do have of possible early Columban activity are all east of Inverness—at Petty, Auldearn, Glenferness and perhaps Kinneddar.

But if Adomnán did come to the Firthlands himself, we might expect to find dedications to him, so it’s interesting that we find one at Urquhart, where he places a church in the Life of Columba.

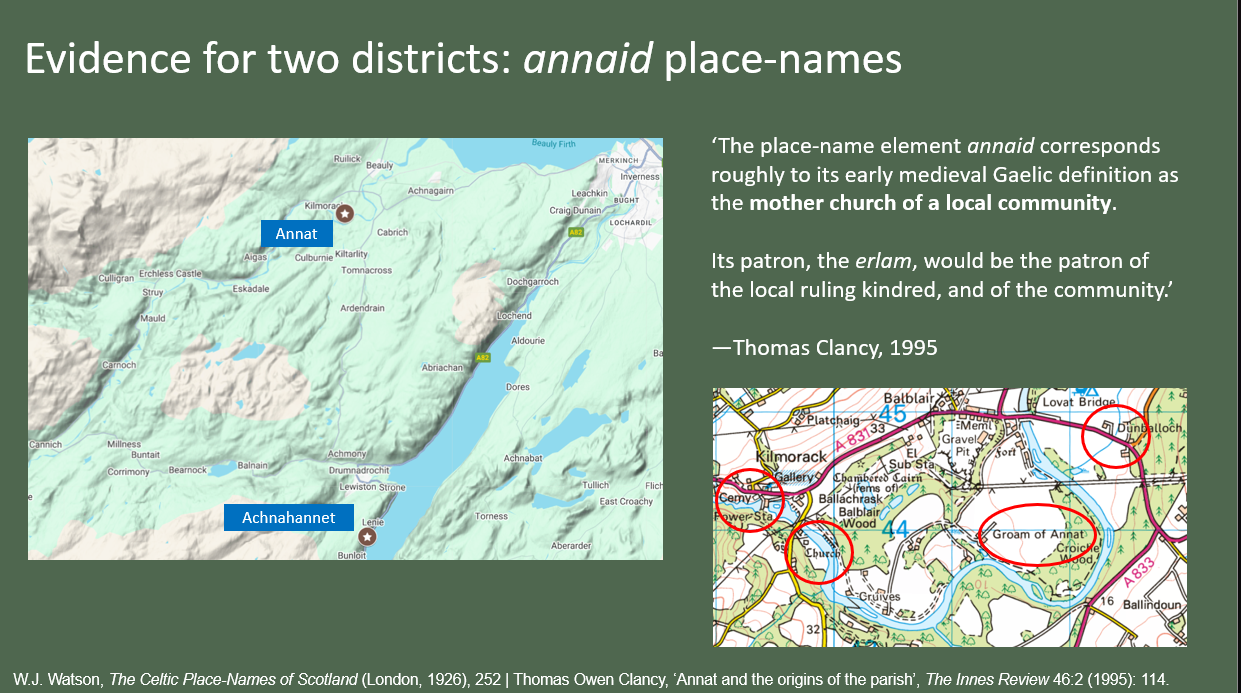

Annaid place-names as indicators of an early mother-church

Another indicator of an early church is the place-name element annaid. Thomas Clancy has shown that annaid place-names tend to indicate the property—but often not the actual site—of a church that was the mother-church of the local community before the parochial system was implemented in the twelfth century.

The place-name scholar W.J. Watson identified two annaid names in this area—Achnahannet, the field of the mother-church, south of Urquhart, and Annat, between Beauly and Kilmorack.

This might suggest that Temple was at one time the mother-church for the district of Urquhart, and that the mother-church for the district of the Aird might have been at Kilmorack, Kiltarlity or Dunballoch, which was the site of Kirkhill parish church prior to 1221.

I should say that in Place-Names of the Aird and Strathglass, Simon Taylor and Jake King cast doubt on the Beauly Annat being an annaid name. They point out that in its earliest recorded instances, in 1571 and 1572, it’s spelled Ainocht. They suggest that the underlying word is aonach, for ‘market, gathering place’.

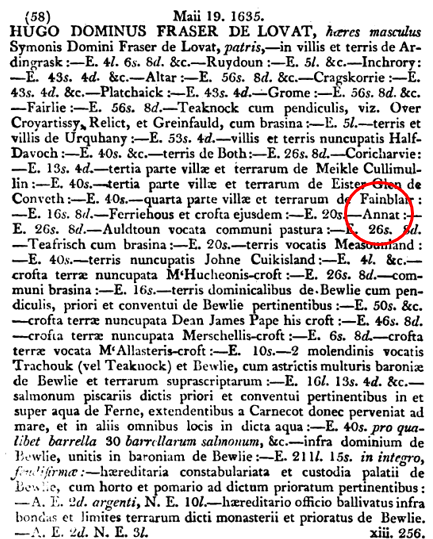

While it's true that the earliest written forms are usually closest to the original name, I think there’s reason to doubt an identification as aonach. It doesn’t explain the final ‘t’ of Ainocht, and the name appears as 'Annat' in Retours of 1635 (below) and 1665, a map of 1757 and the first-edition Ordnance Survey six-inch map of 1872. It’s also close to three ostensibly early church sites. So I’m not quite ready to discount Annat as an annaid name just yet.

(If we had a record of markets or assemblies being held at Annat, that would be good evidence in favour of aonach. So if anyone knows of any, please do comment.)

A hybrid church name at Old Kiltarlity

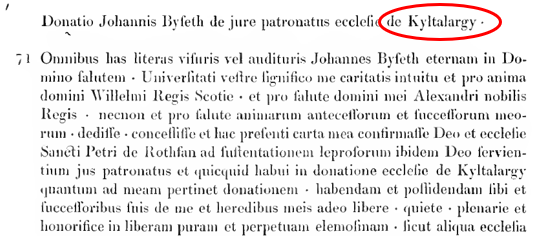

An interesting name in the vicinity of Annat is Kiltarlity, the ‘church of Talorgan’. This is a hybrid name: cill is Gaelic for church, but Talorgan is a Pictish name.

Cill- names were coined throughout the Middle Ages, so a name in cill isn’t necessarily early. But a cill- name with a dedication to an obscure Pictish saint does have an early feel to it, and Kiltarlity appears among the earliest records for the Firthlands, in a charter of John Bisset of the Aird in 1224 (below).

It may hint at a time when Kiltarlity was a pastoral church under a Gaelic bishop, but which venerated a Pictish saint. There’s no Saint Talorgan on record, though, so the identity of the person culted here (and at three or four other places in Scotland) is a mystery.

Another Pictish dedication at Urquhart

And we’ve already seen that the church at Temple had a dedication to another saint with a Pictish name, Drostan. In fact, the Gaelic name for Urquhart even into the eighteenth century was Urchardan mo-Dhrostáin, Urquhart of St Drostan.

According to Irish law, a key requirement for a mother-church of a district was that it should hold relics of the erlam, the founder or patron saint. On that note, a charter of Mary Queen of Scots states that there was a ‘crucifix relic’ of Drostan at Temple. This may be a reference to a relic enshrined with a crucifix ornament, like this bell-shrine from Kilmichael Glassary in Argyll (below).

So it’s possible that at Temple and Old Kiltarlity we may have the mother-churches of the early medieval districts of Urquhart and the Aird.

One point against this, though, is that a place-name in Kil- often denotes a smaller, ‘local’ church, rather than a mother-church. So it’s possible we should look elsewhere for an early medieval mother-church of the Aird. The old church site at Dunballoch, just across the River Beauly from Annat, might be a contender. More research to be done there, I think.

A devotional object from Strathglass

Lastly, I just wanted to note that this hybrid Pictish-Gaelic early Christian landscape would provide a good context for the stunning shale pendant found at Breakachy near Beauly in 1877.

It’s fashioned like a miniature Pictish cross-slab, with a Pictish serpent symbol and cross symbol on the reverse.

This was a devotional item for an elite eighth-century Christian, perhaps even a devotee of Talorgan, Drostan or Curetán, the most prominently-culted local saints.

Conclusion: two 7th-century túatha in the Life of Columba?

So to summarise, Adomnán’s Life of Columba seems to give us a glimpse of two late seventh-century districts in Inverness-shire, corresponding to Urquhart and the Aird. This hypothesis is supported to some degree by archaeology, place-names, landscape and objects.

Each district seems to have had a secular stronghold and (perhaps) a mother-church. And both, along with Strathglass, seem to have formed part of Curetán’s episcopal jurisdiction based at Rosemarkie—which seems to have been a Gaelic bishopric in Pictland.

And one last thought. While Adomnán shows both districts as inhabited by pagan Picts, he paints Urquhart as friendly to Columba, and the Aird as hostile. We might want to think about why that was.

Was the ruler of the Aird trying to thwart the Columban church in some way in Adomnán’s time, or even lapse back into pagan practices? Was it necessary for Adomnán to emphasise the superior power of the Christian faith, or the power of Columba who had wielded it in that area?

I don’t have answers to these questions yet, but they’ll form part of my continued research into the early church in the Moray Firthlands.

Thank you very much for reading!