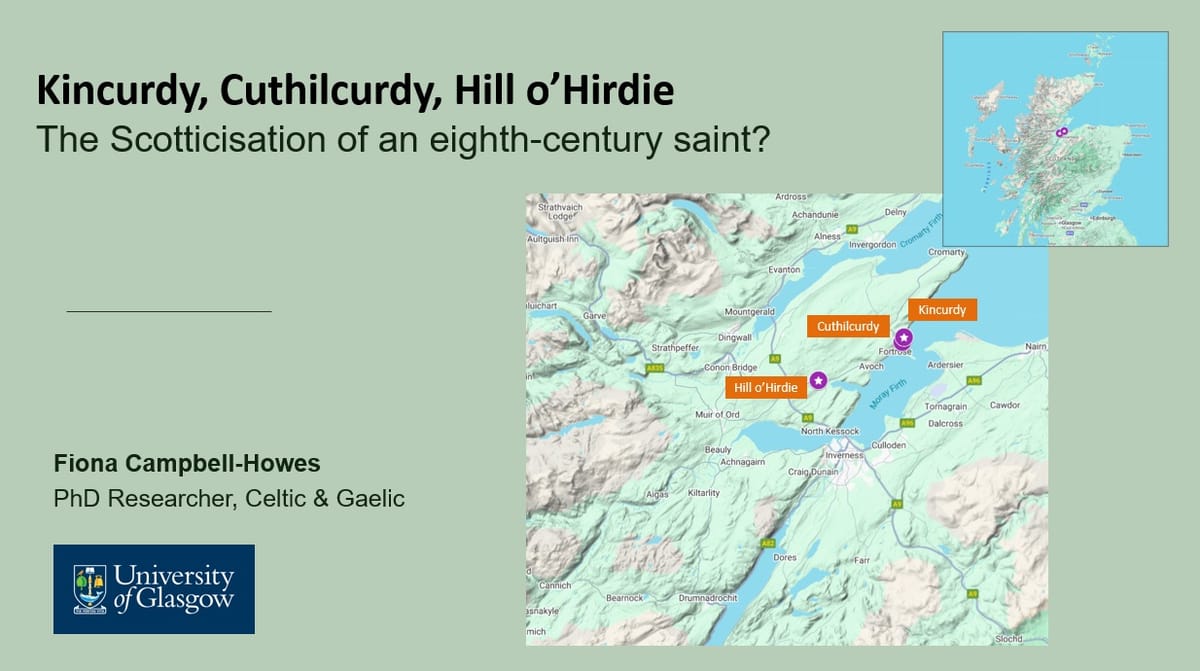

Kincurdy, Cuthilcurdy, Hill o’ Hirdie: Evidence of a Scots cult of St Curetán?

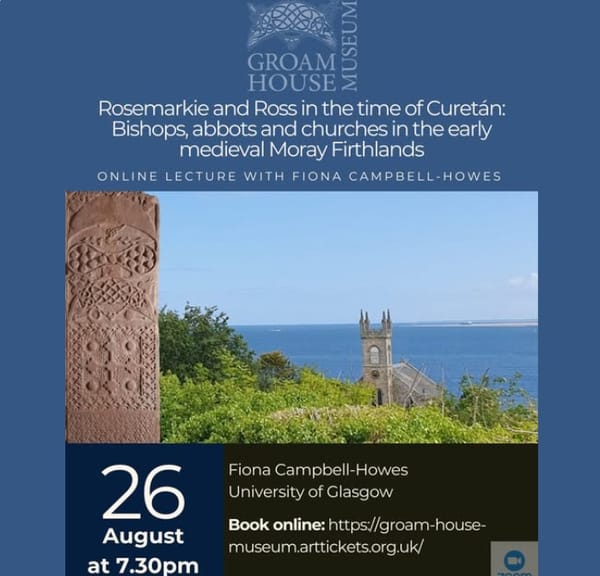

This post is more or less the transcript of a talk I gave this afternoon at the Scottish Place-Name Society Autumn conference, which took place on Zoom. Many thanks to Simon Taylor, Bill Patterson, Sofia Evemalm-Graham, Morag Redford and all of the other speakers for such an interesting day of talks.

My abstract should help to set the scene:

The area around Rosemarkie on the Black Isle has long been noted as a cult centre for St Curetán, a bishop who is reliably attested as being active in the Moray Firthlands around the turn of the eighth century. Three Black Isle place-names appear to preserve his name in Scotticised form: Kincurdy, Cuthilcurdy and Hill o’ Hirdie, suggesting that his cult survived into the late Middle Ages or later. This paper will examine whether these names do contain Scotticisations of Curetán, and what they can tell us about the longevity of Curetán’s cult.

(Footnotes are included in the slides, which you can click to enlarge.)

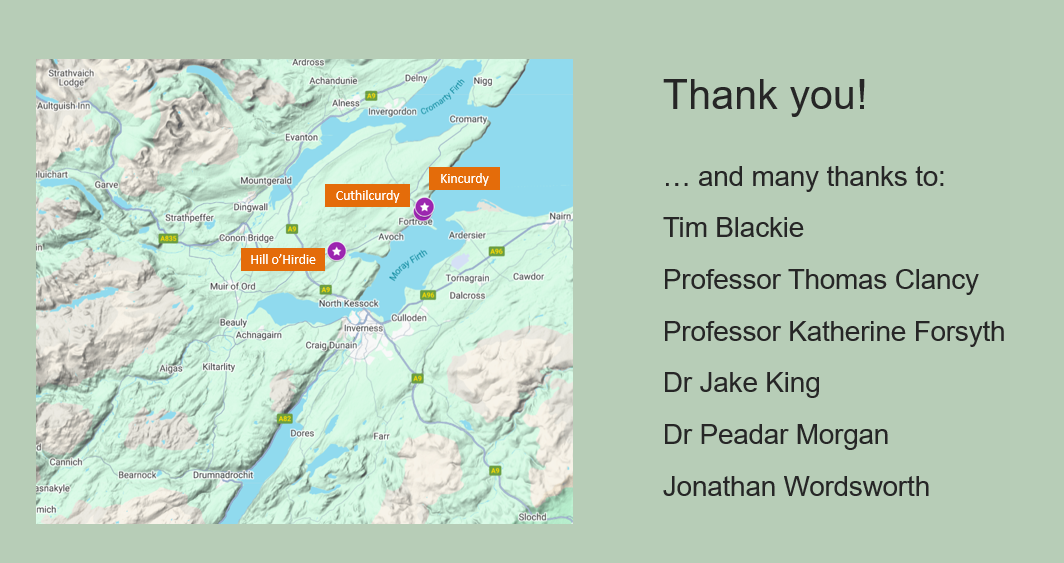

Many thanks to the Scottish Place-Name Society for the opportunity to speak today.

I’m going to discuss three place-names that I’ve been looking at as part of my PhD research into Curetán, an eighth-century saint who is heavily associated with Easter Ross, the Black Isle, and the early medieval ecclesiastical site at Rosemarkie.

I’m a historian, not a historical linguist or toponymist, and I'm also not a Gaelic speaker, so I’d love to hear any thoughts on what I’m going to present.

A (tiny) bit about Curetán

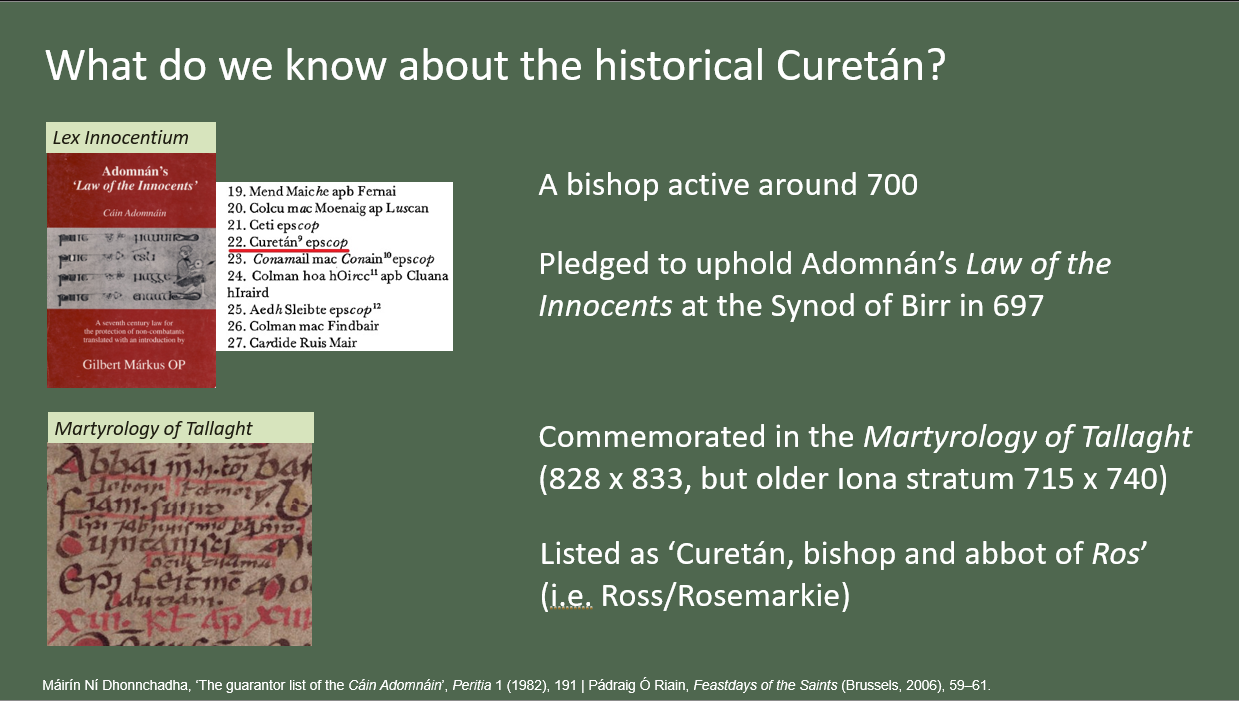

Unlike many of Scotland’s early medieval saints, we know a tiny bit about the historical Curetán. In 697 he was a guarantor of the Lex Innocentium, a law code drawn up by Adomnán, the ninth abbot of Iona, and promulgated that year at the Synod of Birr in Ireland. In the guarantor list for that law code, he is listed just as epscop, ‘bishop’.

He's also commemorated in the Martyrology of Tallaght, a calendar of saints’ days compiled at the monastery of Tallaght near Dublin between 828 and 833. Pádraig Ó Riain has demonstrated that Curetán’s entry came from an older calendar that was kept on Iona between 715 and 740. It records Curetán as bishop and abbot of Ros—a reference to Ross, or Rosemarkie, or both.

Place-names containing Curetán's name

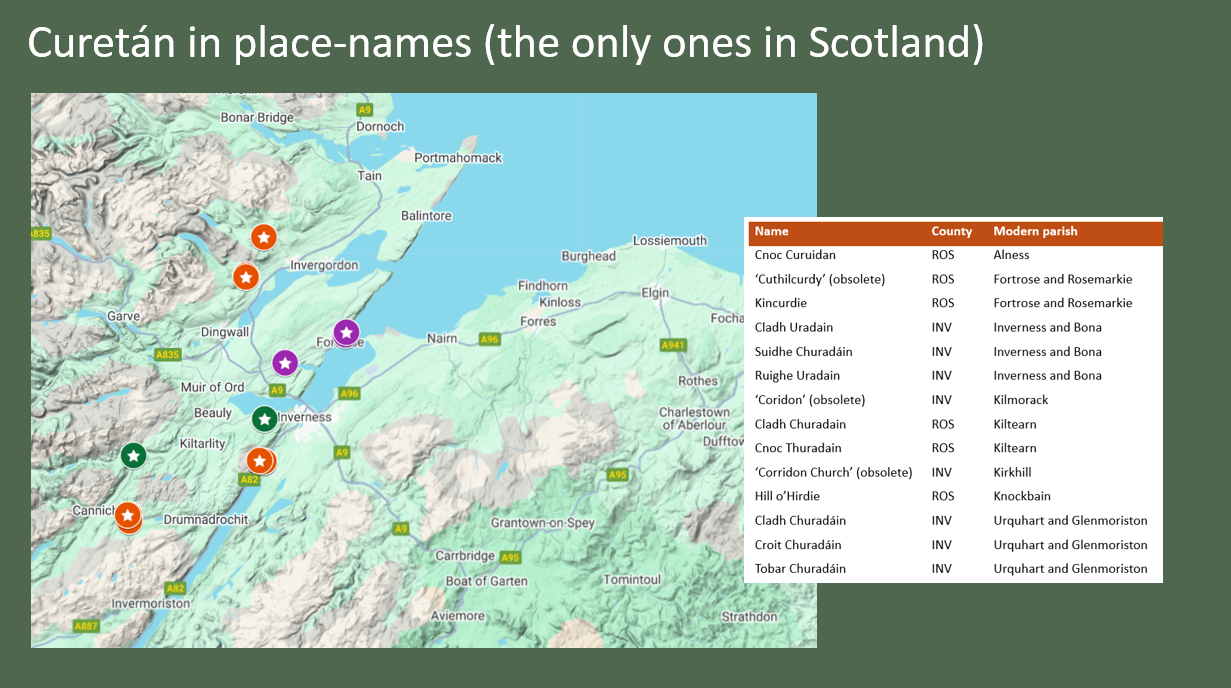

His status as bishop of Ross seems to be supported by the distribution of 14 place-names that appear to contain his name - the only such place-names anywhere in Scotland.

They occupy an unusually compact area, west of the Great Glen Fault, north of Glenurquhart, and south of the Alness River.

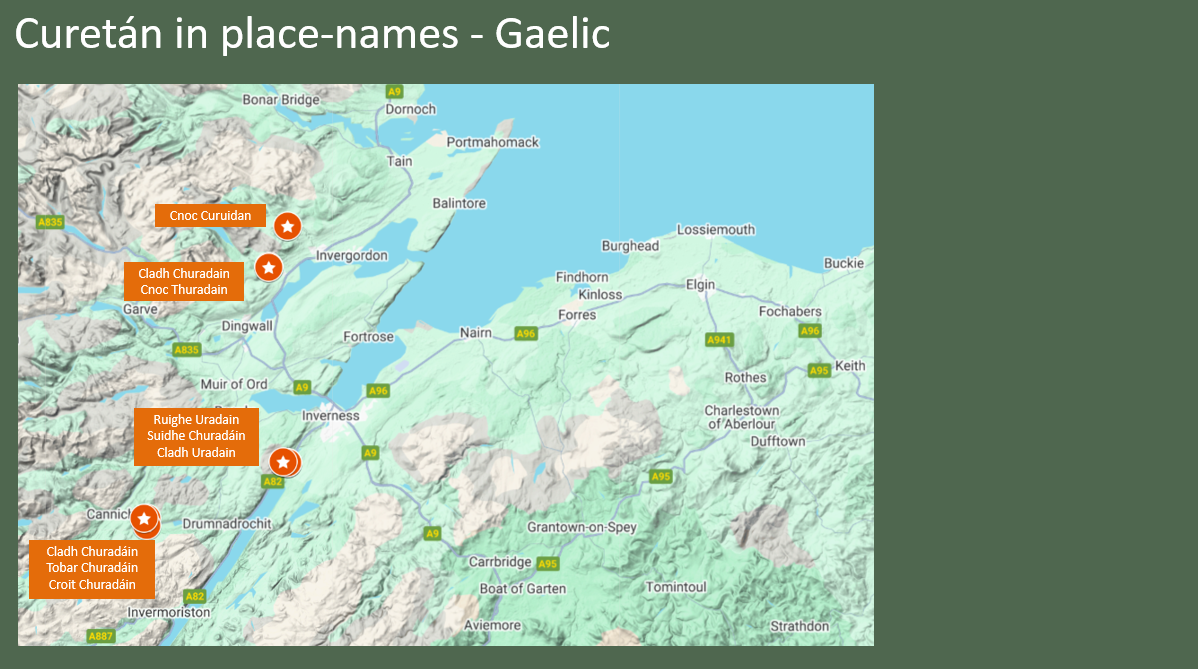

Nine of these place-names are in Gaelic. They preserve his name as Curetán, with the initial C appearing in a variety of lenited and unlenited forms.

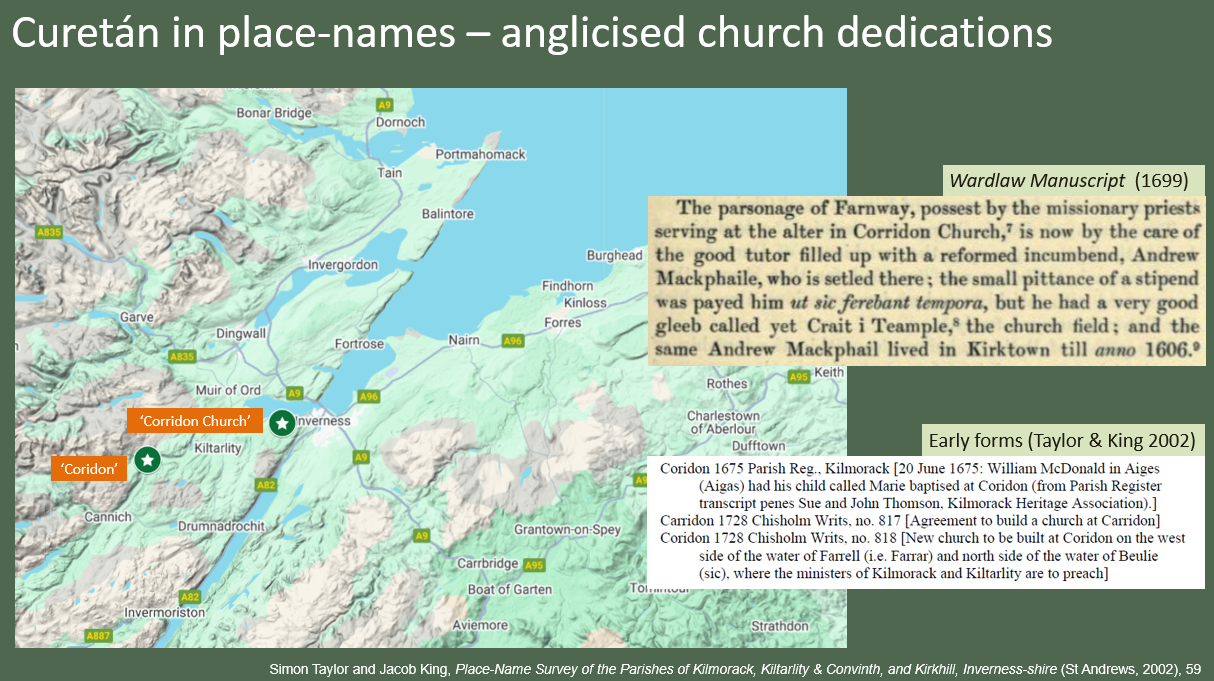

Two of them are, or were, church names rather than place-names, and preserve Curetán’s name in an anglicised form. 'Corridon Church' was at Kirkton in the Aird, and until 1728 the church at Struy in Strathglass was known as ‘Coridon’.

The remaining three names are, to my mind, more problematic, and they’re the ones I’d like to focus on today.

Three Black Isle place-names

They’re all on the Black Isle, where Curetán had his see at Rosemarkie. We have Hill o’Hirdie near Munlochy; Kincurdy, now a substantial house just to the north of Rosemarkie, and an obsolete ‘Cuthilcurdy’, somewhere in the vicinity of Rosemarkie.

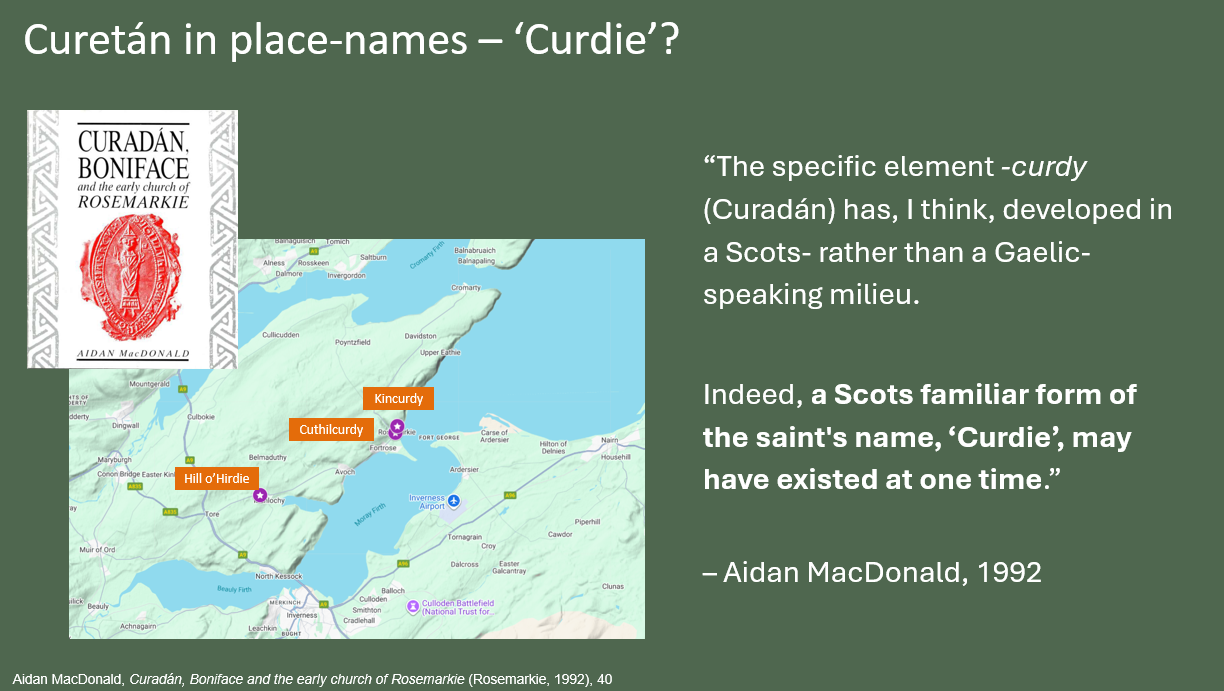

In 1992, Aidan MacDonald considered all three names in his Groam House Lecture Curadán, Boniface and the Early Church of Rosemarkie. He suggested that they might all contain an element 'Curdie'; a hypocoristic (diminutive or familiar) Scots form of the name Curetán.

If these names do contain a familiar form of Curetán, it would suggest that an active cult of this saint survived the language and culture shift from Gaelic to Scots in the Black Isle. That shift began probably in the thirteenth century—500 years after Curetán’s floruit.

That’s an interesting proposition, for a couple of reasons.

First, there are no ‘Curdy’ place-names in the rest of the Curetán place-name zone. In fact there are no hypocoristic forms of his name in these place-names at all—which is interesting in its own right, but not a topic for today.

Second, I haven’t found a single knowing textual reference to Curetán, under any version of that name, anywhere in the Curetán place-name zone prior to 1900.

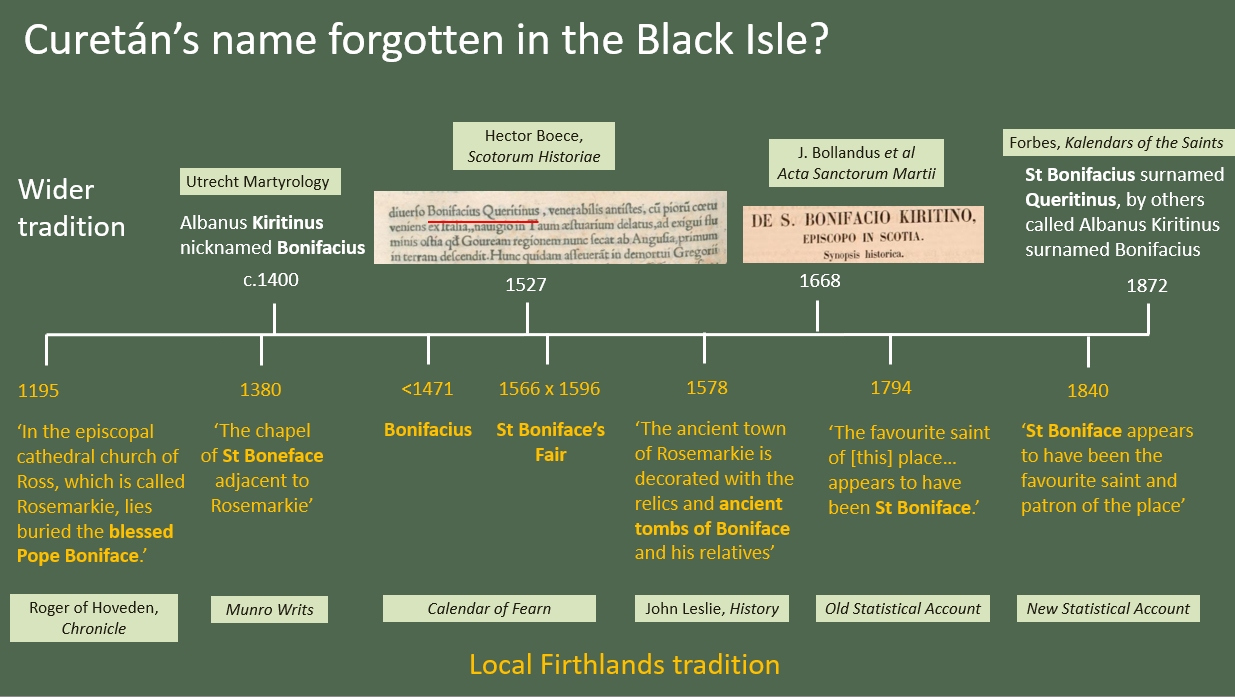

From 1195 to 1900 (in yellow along the bottom of the above slide) he is always referred to locally by his alter ego of Boniface, which he seems to have acquired in or by the 12th century.

Various Irish, Scottish and continental sources (along the top in white) knew that Boniface was also called something like Curetán, which gets Latinised to Kiritinus and Queritinus, but this seems to have been forgotten in the Moray Firthlands.

But it’s possible that a cult of Curetán might have survived in oral tradition in the Black Isle, if not in the written record. So I approached the three ‘Curdy’ names with that possibility in mind.

Hill o'Hirdie and the Munlochy Clootie Well

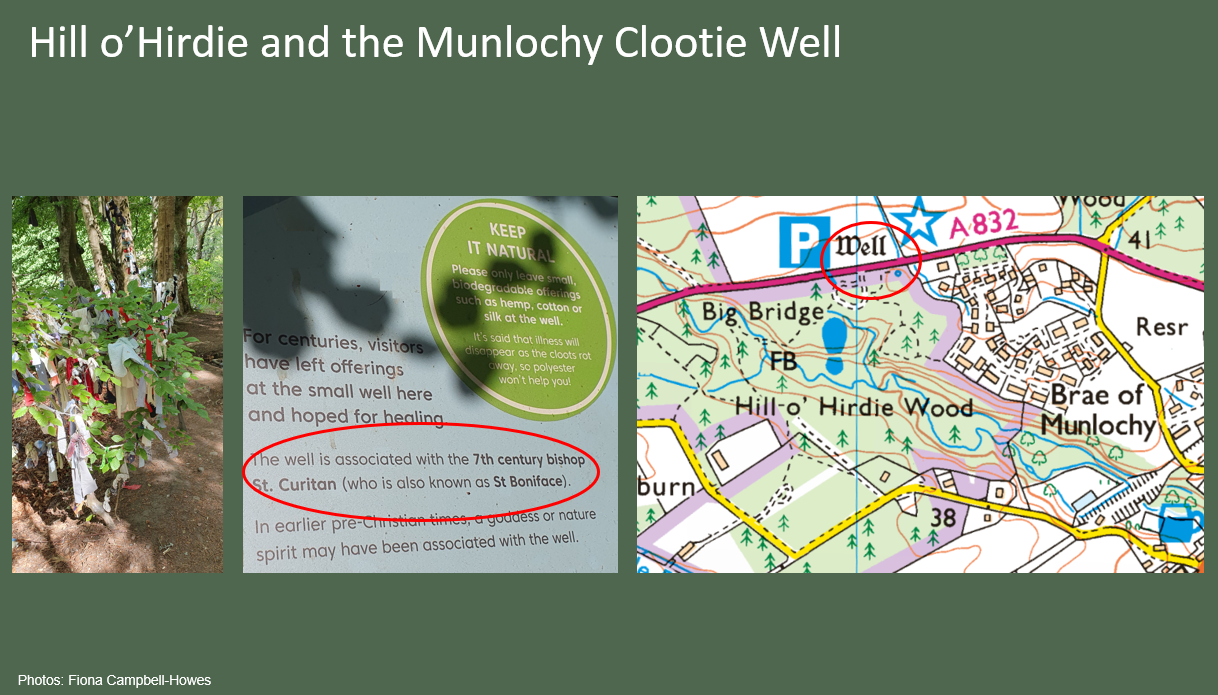

I'm going to start with Hill o’Hirdie. This is a very well-known site, as it’s the location of the famous Munlochy Clootie Well.

The signage at the well (above) makes an explicit link to Curetán. But the association is painted in rather vague terms and it’s not clear what the well has to do with our eighth-century bishop.

The well is located halfway up a small hill, which on the modern OS map is located in Hill o’ Hirdie Wood. It’s this name that Aidan MacDonald suggested preserves a Scots familiar form Curdie.

But does it? When I started to look for early forms of the hill name, some odd things quickly became apparent.

The elusive Hill o'Hirdie

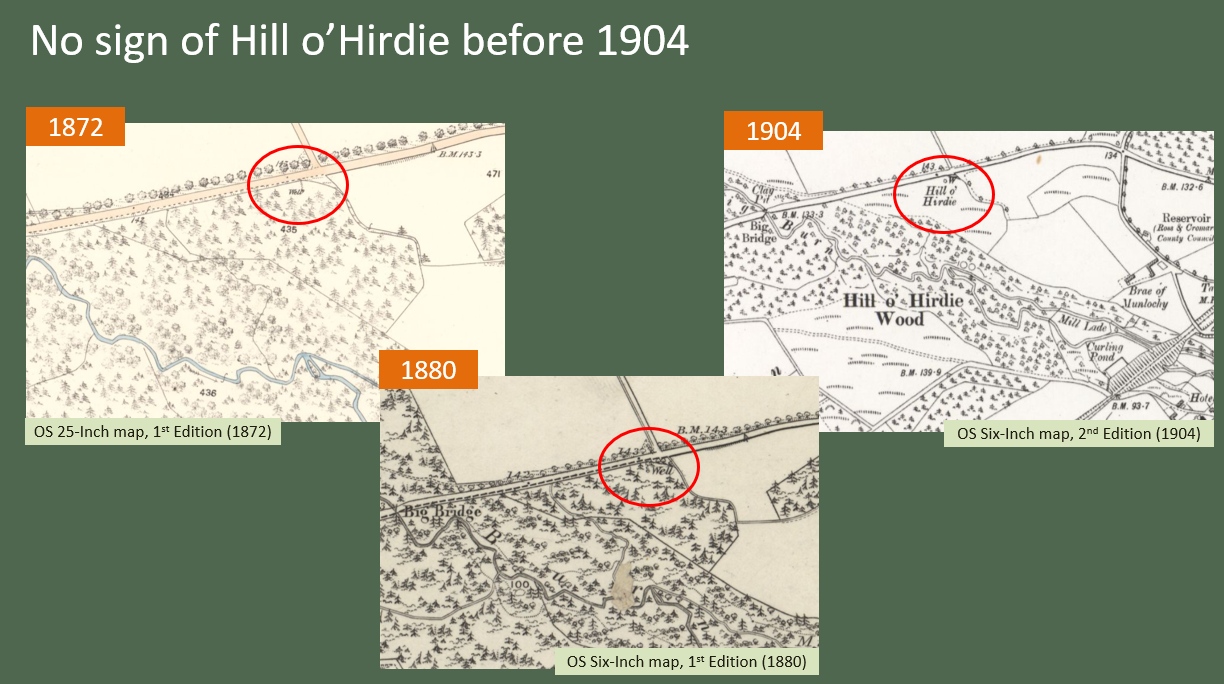

First, there’s no sign of a Hill o’Hirdie on any map prior to the 1904 OS six-inch second edition.

The 25-inch first edition of 1872, and the 6-inch first edition of 1880, show no name for the hill or the wood it stands in, and the well is just marked as an undifferentiated ‘Well’:

The first-edition OS maps got their place-names from the local surveys conducted in the 1870s and entered into the OS Name Books. And in the OS Name Book for Kilmuir Wester and Suddie, as the parish was then, there’s no mention of a Hill o’Hirdie or a clootie well.

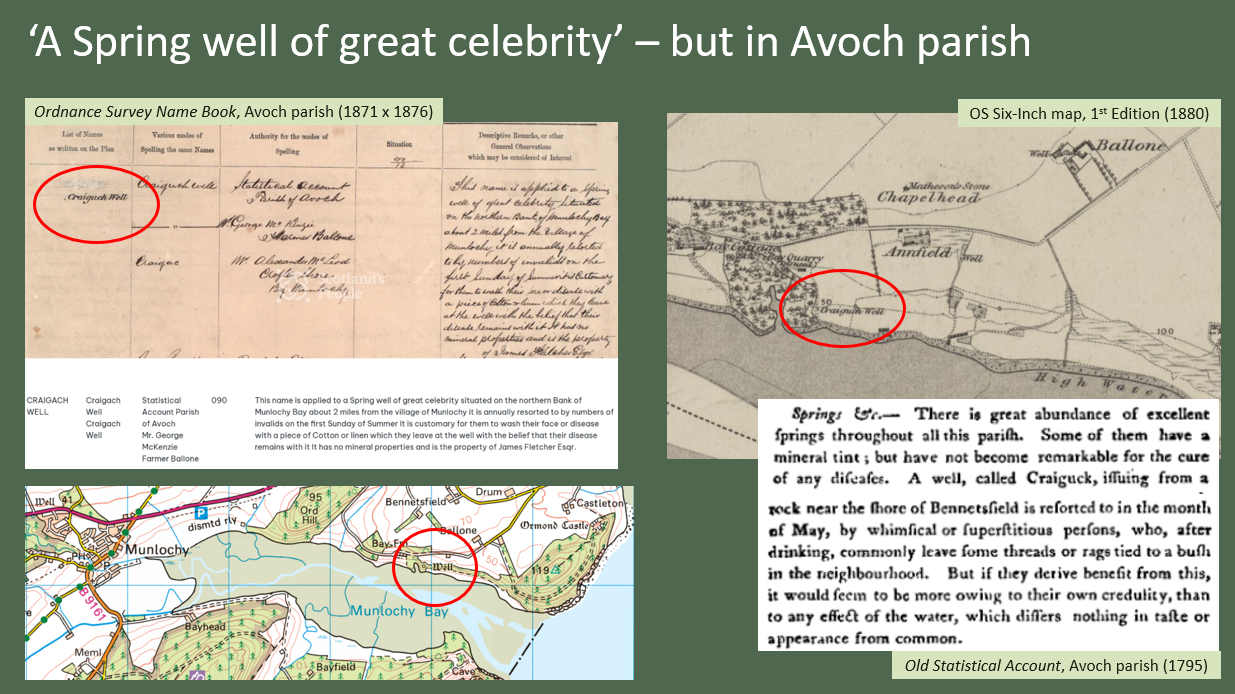

The survey did record a clootie well ‘of great celebrity’ in the area, but it’s on the shore of Munlochy Bay in neighbouring Avoch parish, and it’s called the Craiguch Well.

I also drew a blank with the Old and New Statistical Accounts. Here again, I found the Craiguch Well, but nothing about a Hill o’Hirdie or a clootie well at Munlochy.

So where had this possible Curetán toponym and its tradition of an ancient well come from?

Some illuminating newspaper correspondence

An illuminating blog by Jake King provides an answer. In researching the Munlochy Clootie Well, Jake unearthed some local newspaper correspondence from 1900 between John Sinclair, minister at Kinloch Rannoch, and the eminent toponymist William Watson, then in his mid-thirties.

It turns out that the association of Hill o’Hirdie with Curetán is no older than this correspondence, and is almost certainly misguided. But we have to go back to the 18th century to see why.

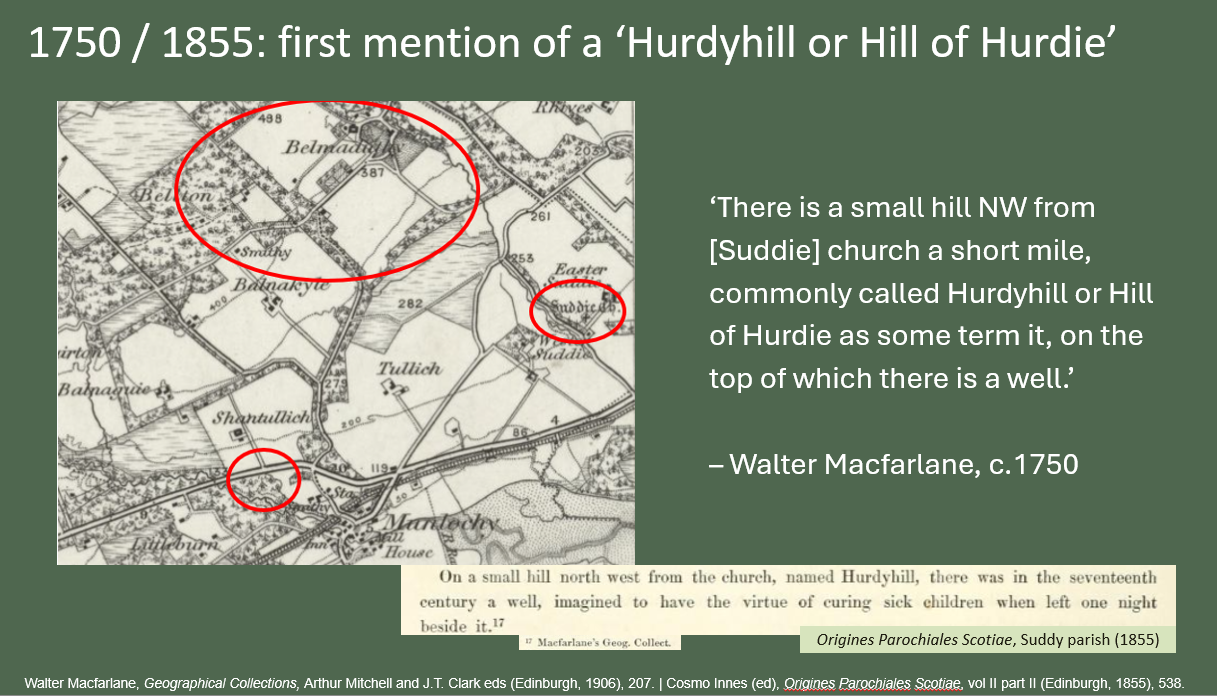

Around 1750, the antiquary Walter Macfarlane amassed a collection of topographical information that had been sent to him by local informants from all over Scotland.

One informant had supplied him with this information about Suddie parish, as it was then:

‘There is a small hill NW from [Suddie] church a short mile, commonly called Hurdyhill or Hill of Hurdie as some term it, on the top of which there is a well.’

It's notable that this Hurdyhill is north-west of Suddie church, that its popular names are given in Scots, not Gaelic, and that the well—which is reputed to be the haunt of fairies—is on top of the hill, not halfway up it.

This doesn’t match with the location of the Clootie Well at Munlochy, which is south-west of Suddie church and halfway up the hill.

This information was cited in 1855 in the Origines Parochiales Scotiae, Cosmo Innes’s epic project to research the history of every parish in Scotland.

The hill moves to Munlochy

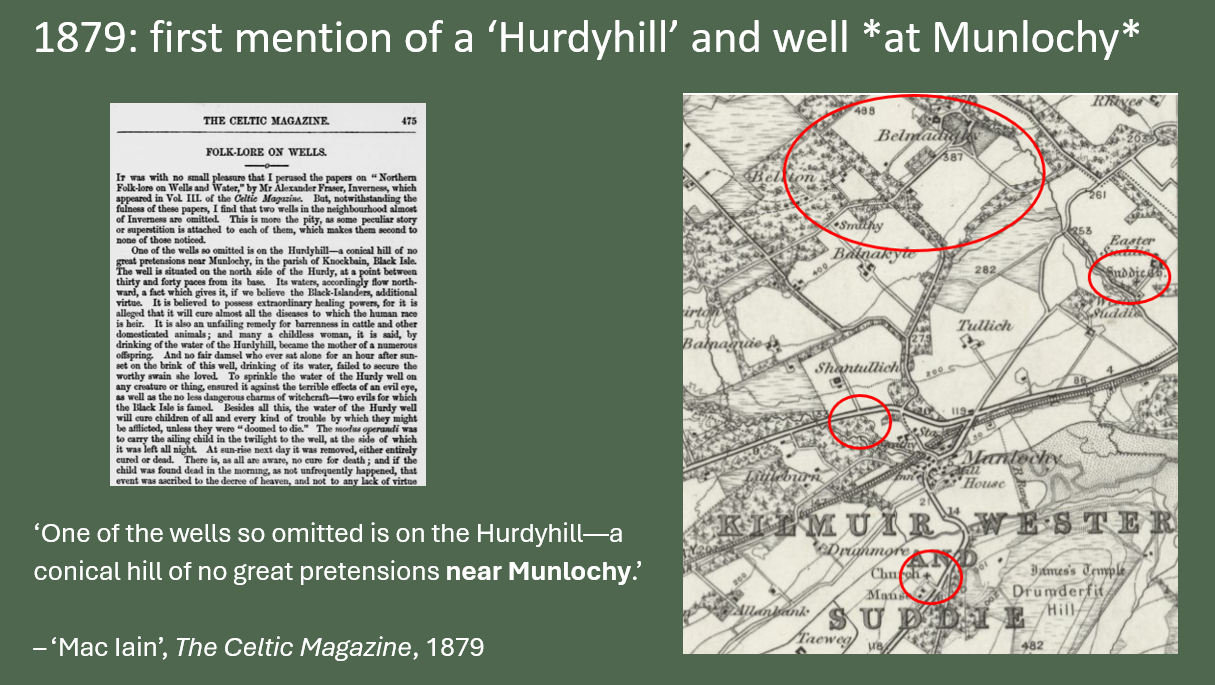

In 1879, a person with the pseudonym ‘Mac Iain’ writes to the Celtic Magazine about the well on Hurdyhill. Again, the hill name is only given in Scots, not Gaelic.

‘Mac Iain’ locates both hill and well at Munlochy, not north-west of Suddie church. This is the earliest reference I’ve found to the Hurdyhill being located at Munlochy.

Possibly he or someone else had misread OPS, and thought that the hill was north-west of Knockbain church (circled bottom centre of the map above), which had replaced Suddie as the parish church in 1764.

First sight of a Gaelic form of Hurdyhill

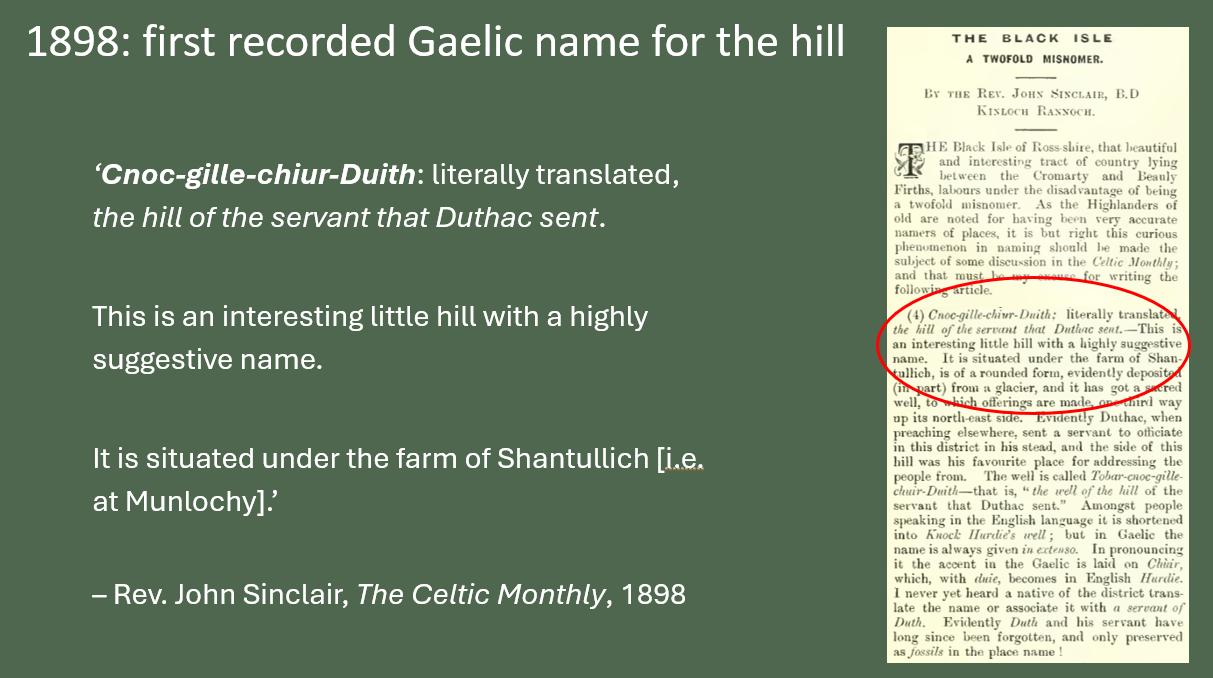

In 1898, Reverend John Sinclair writes a long article for the Celtic Monthly, attempting to prove that the Black Isle – an t-Eilean Dubh in Gaelic – is actually St Duthac’s Isle, Eilean Duthaich. As evidence, he lists 20 Black Isle place-names that he considers to have Duthac’s name in them.

One of these names is Hurdyhill, for which he gives a Gaelic form: Cnoc-gille-chiùr-Duith, which he translates as ‘the hill of the servant that Duthac sent’. This seems to be the first time a Gaelic form of the hill name enters the textual record.

Like ‘Mac Iain’ in 1879, Sinclair places the hill and its well at Munlochy.

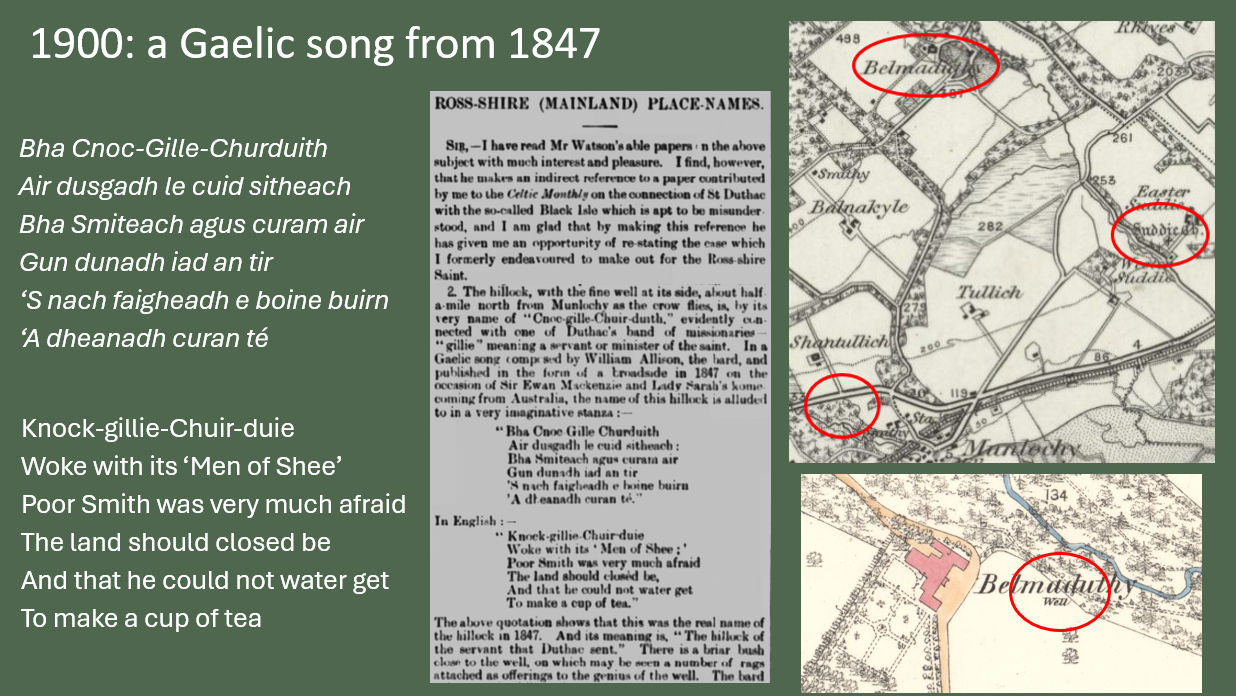

A Gaelic homecoming song from 1847

In 1900, Sinclair writes to the Northern Chronicle about Duthac names. This time he quotes a verse of a Gaelic song that he says was written in 1847 to celebrate the homecoming from Australia of the new laird of Belmaduthy, Ewan MacKenzie.

It seems to be from this song that he has learned the Gaelic form of Hurdyhill, which he is still convinced means ‘the hill of the servant that Duthac sent’. I’ve put the verse and Sinclair’s English translation below.

A few things strike me about this song. First, it was composed for the laird of Belmaduthy, which, like Macfarlane’s Hurdyhill, is a mile or so north-west of Suddie Church. It seems very likely to me that the original Hurdyhill was on the Belmaduthy estate.

It may even have been the hill on which Belmaduthy House was built in the early 19th century. There’s a well just in front of it, marked on the 25-inch first edition map above.

(Was this perhaps the well where Smiteach would fetch water for his tea?)

Second, the tone strikes me as being rather whimsical. On that note, the bard, William Allison, has Gaelicised the name ‘Smith’ as Smiteach. I suspect this is a reference to John Smith, the father of two Belmaduthy labourers who accompanied Ewan Mackenzie to Australia (see page 433 of this paper).

This makes me strongly suspect that Allison has also humorously Gaelicised the name Hill o’ Hirdie as Cnoc-gille-churduith, and that the Scots name ‘Hurdyhill or Hill of Hurdy’ given by Walter Macfarlane’s informant is the authentic one.

If so, then the ‘gille’ that Sinclair saw as meaning ‘servant’ is really just the phrase ‘hill o’’. And ‘chùr-duith’, which Sinclair saw as meaning ‘sent by Duthac’, is the Scots word ‘Hurdy’, which I gather means ‘buttock’. A bottom-shaped hill, perhaps?

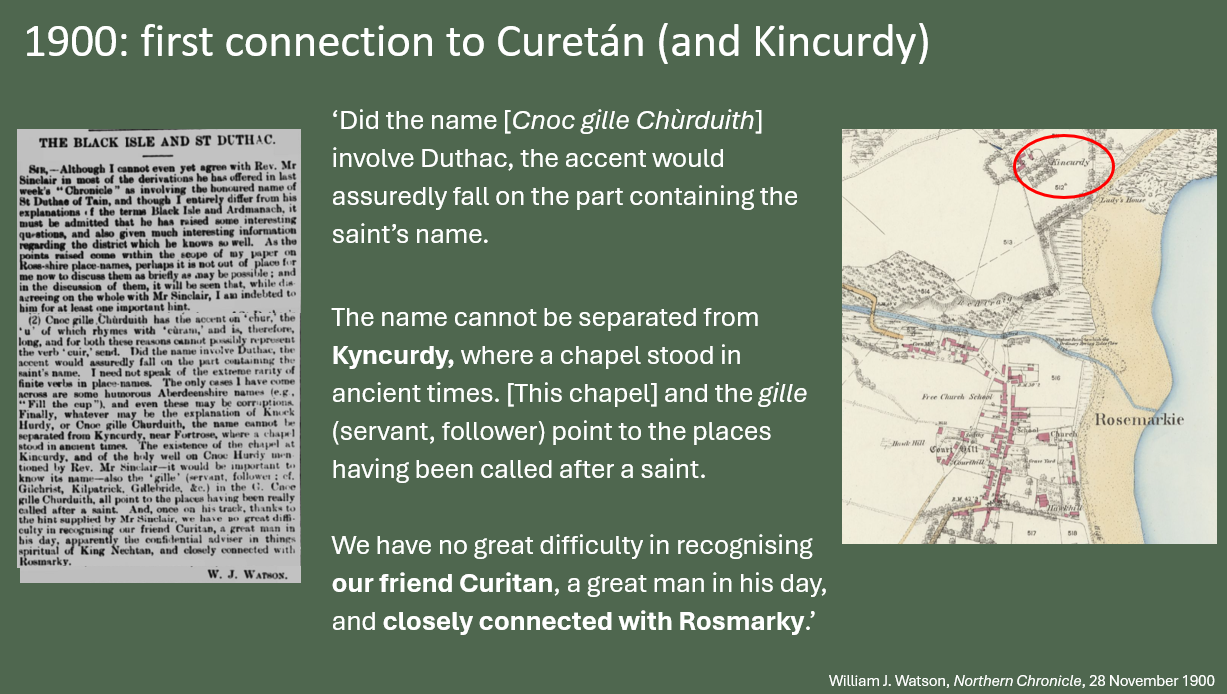

W.J. Watson and the Curetán connection

Sinclair’s letter receives a reply from W.J. Watson. He explains that the name can’t possibly contain Duthac, but he is intrigued by the ‘gille’ and ‘chùr’ elements.

He interprets gille as the devotee of a saint, and compares the chùr with Kincurdy near Rosemarkie (circled in red above). He concludes that both names refer to Curetán, who is ‘closely connected with Rosemarky’.

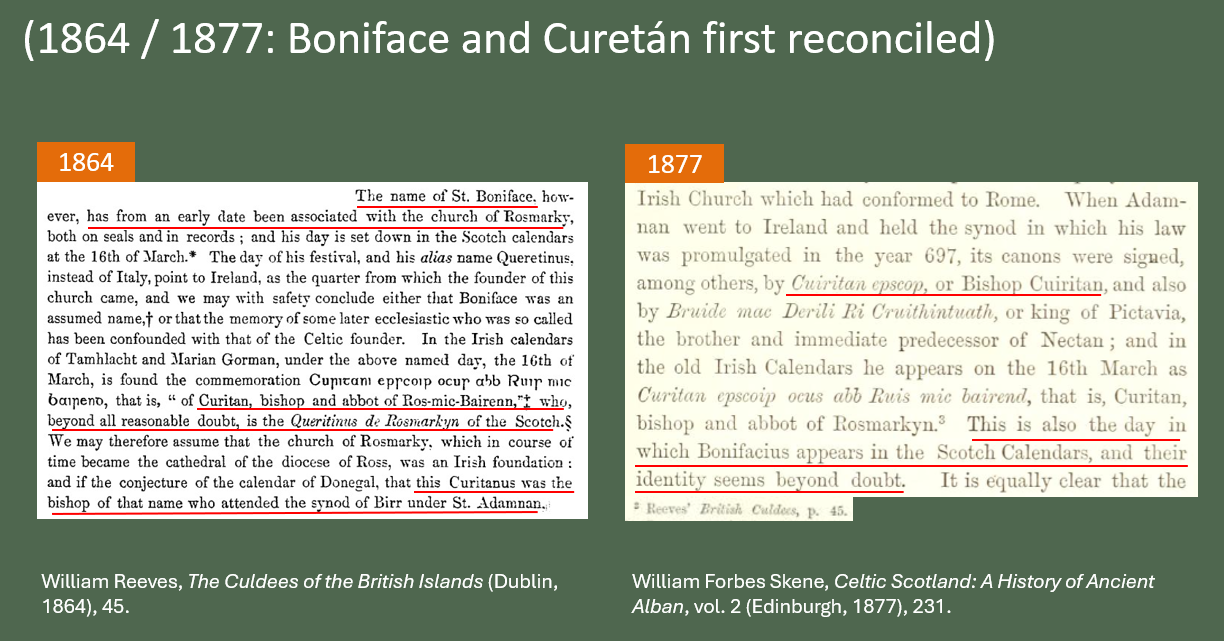

As an aside, Watson omits to say that the connection of Curetán with Rosemarkie was a relatively recent development in 1900. It was only in 1864 that the Irish scholar William Reeves had put two and two together and realised that the Boniface culted on the Black Isle was the bishop Curetán who guaranteed the Lex Innocentium in 697.

Reeves's work was cited by William Forbes Skene in his 1877 Celtic Scotland, and it seems to be from Skene that Watson learned of the connection.

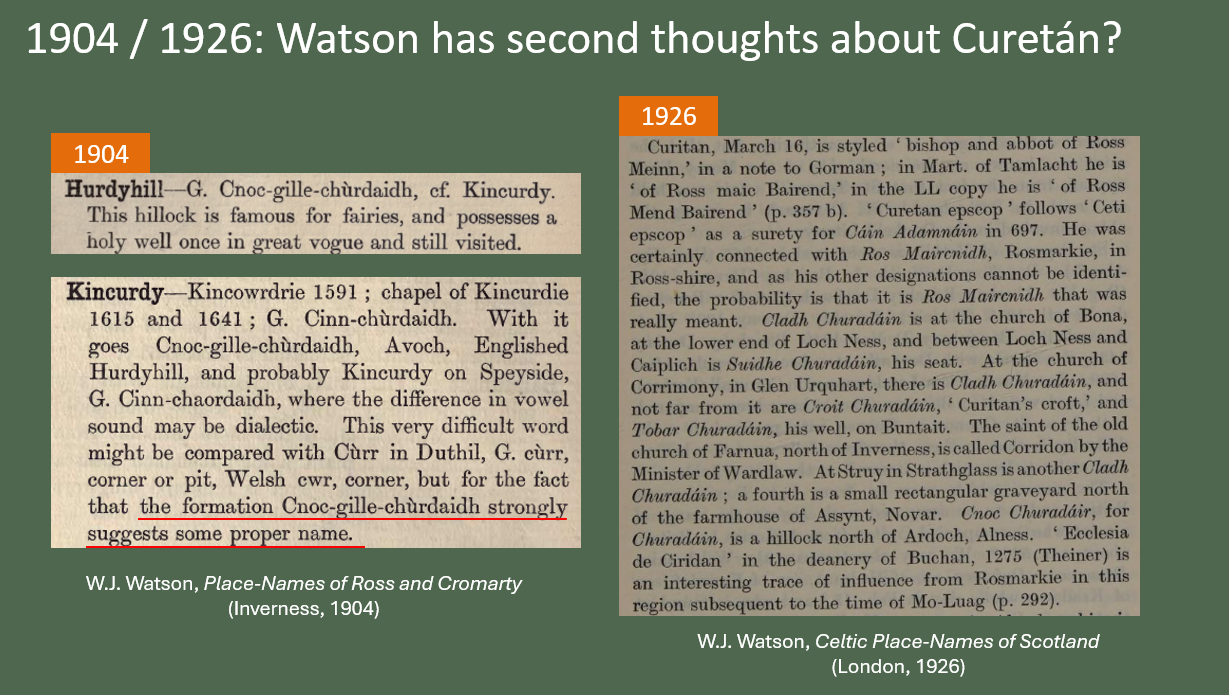

So it’s this letter of Watson’s from 1900 that first connects both Hill o’Hirdie and Kincurdy with Curetán. But it’s notable that he never mentions this association again.

When he publishes his Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty in 1904, he still notes the ‘gille’ of Cnoc-gille-chùrdaidh as suggesting ‘some proper name’, but he seems to have become uncomfortable with linking chùrdaidh and the curdy of Kincurdy to Curetán specifically.

And when he lists Curetán place-names in his 1926 Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, he omits both names altogether.

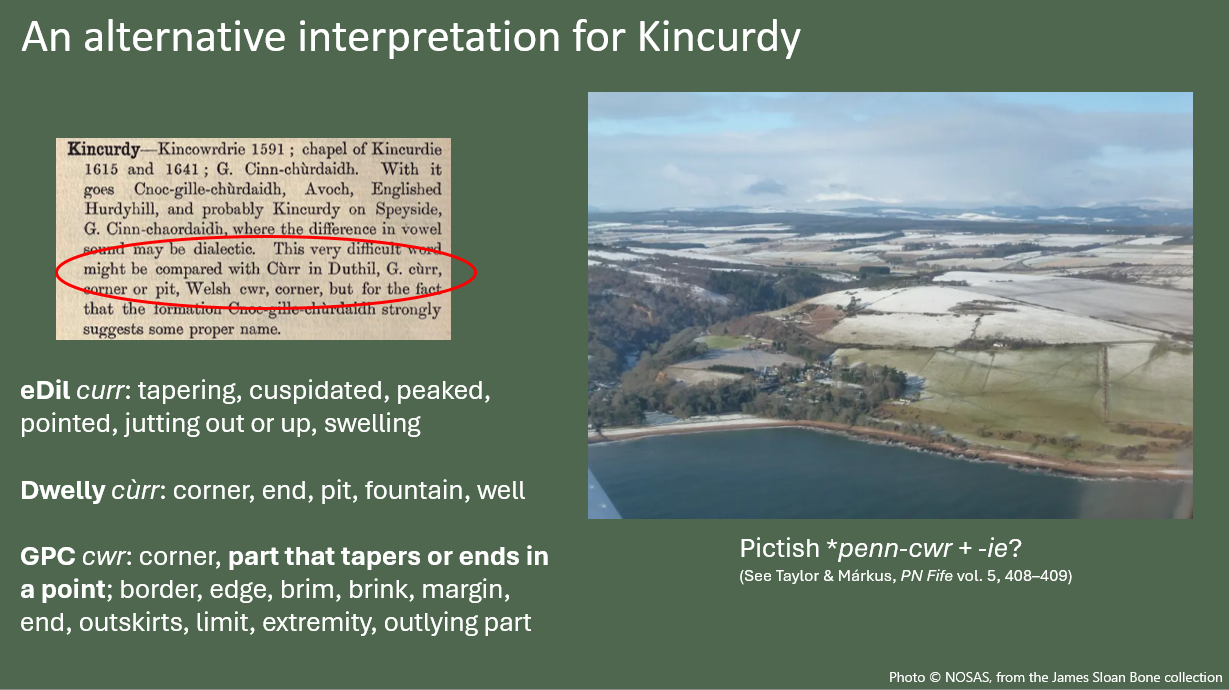

An alternative derivation for Kincurdy

In Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty Watson had offered an alternative etymology for Kincurdy, based on ‘Gaelic cùrr, ‘corner’ or ‘pit’, or Welsh cwr, ‘corner’’. I think it’s worth considering that possibility.

The aerial view of Kincurdy above shows that it sits at the tapering end of a point of higher land above the Fairy Glen and Rosemarkie Bay. The location fits particularly well with the Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (GPC) definition, which might suggest that Kincurdy was in origin Pictish *penn-cwr, with locative -ie ending.

(That's my amateur interpretation at least! I’d be interested in any thoughts.)

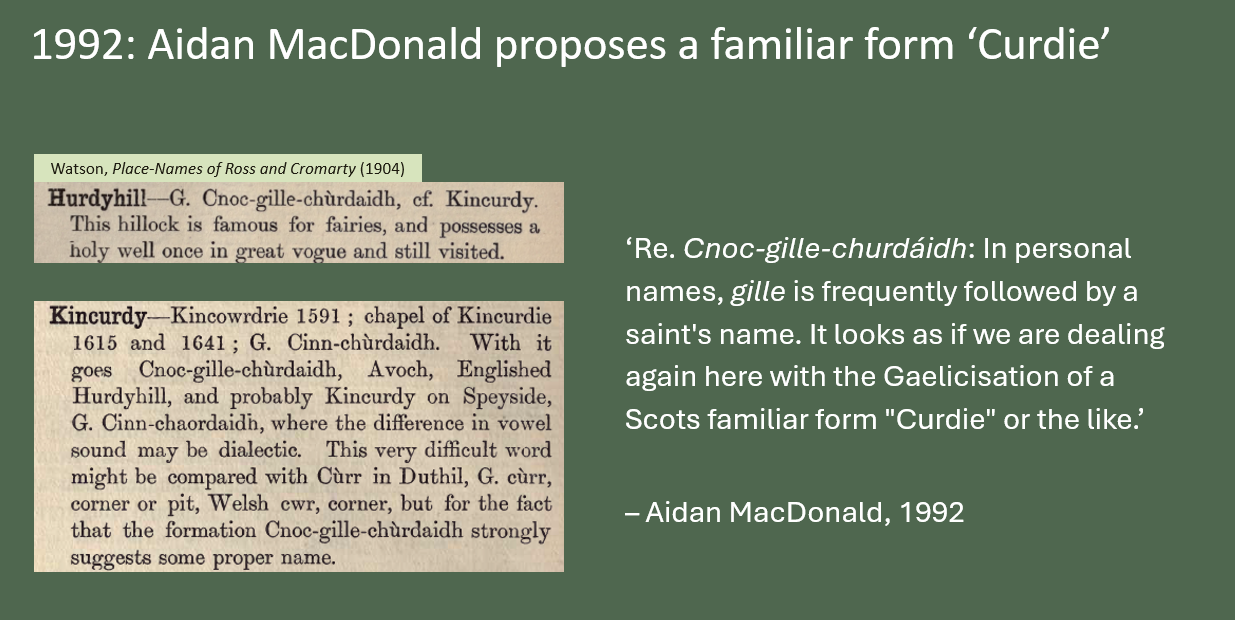

Aidan MacDonald revives the theory

In 1992, for his Groam House Lecture, Aidan MacDonald resurrected the idea of Hill o’Hirdie and Kincurdy as Curetán names.

He noted Watson’s suggestion in Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty that Cnoc-gille-chùrdaidh seems to contain the word gille, and added that ‘churdaidh’ in that name and Kincurdy could be a familiar form of Curetán.

He was unaware, I think, that Watson had already proposed this in 1900 and then dropped it.

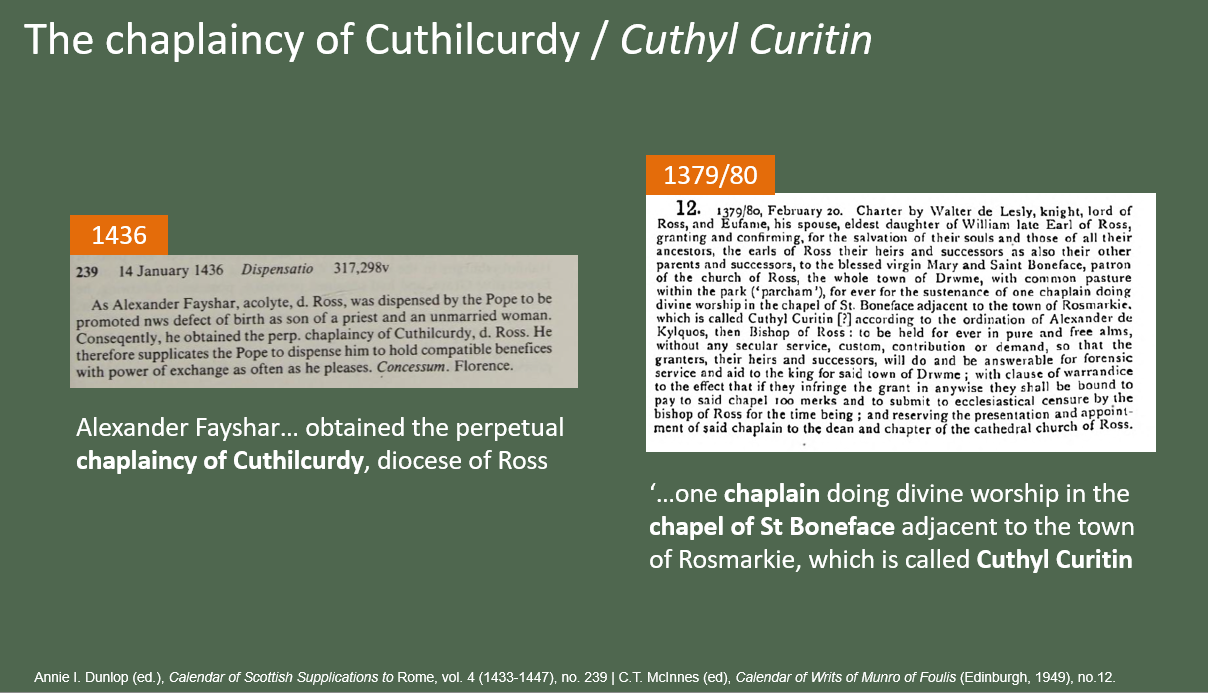

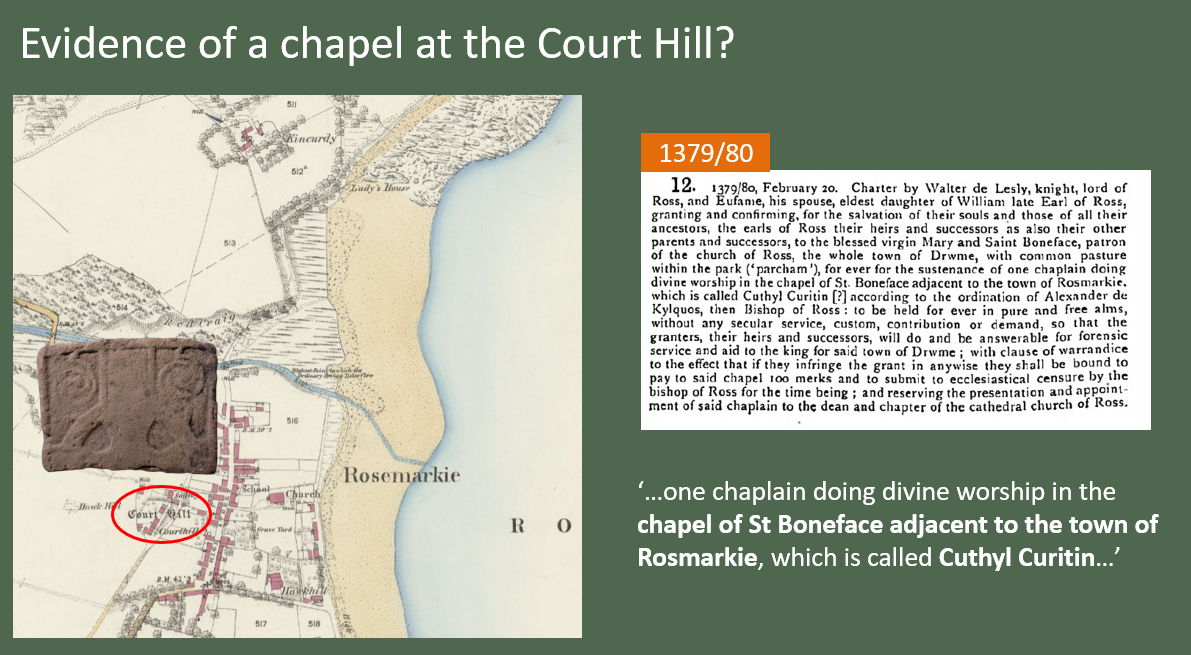

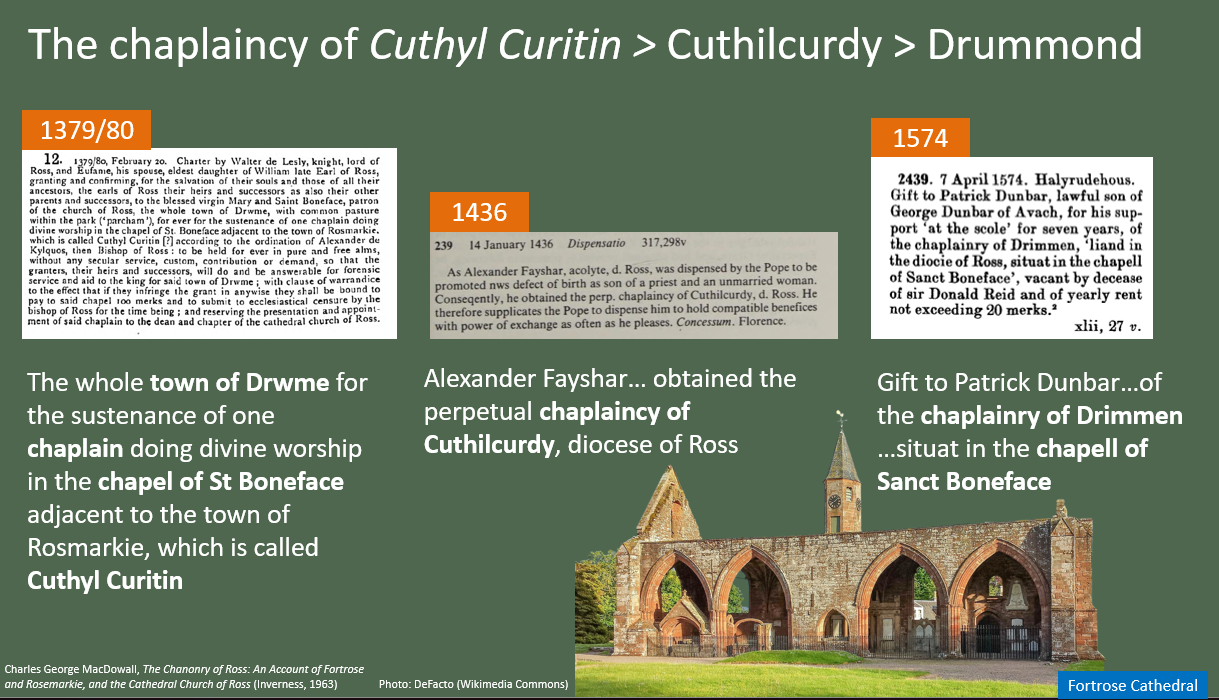

To support his argument, he brought a third, lost place-name into the mix. In a papal dispensation of 1436, one Alexander Fayshar is noted as having obtained the perpetual chaplaincy of a place named Cuthilcurdy.

In an earlier charter of 1380, we see the genesis of this chaplaincy. Here, Walter de Lesly, earl of Ross, and his wife Euphemia, grant the farm and pasture of ‘Drum’ – modern-day Drummond near Evanton on the Cromarty Firth – forever, to pay for a chaplain to do divine worship in

...the chapel of St Boneface adjacent to the town of Rosemarkie, which is called Cuthyl Curitin

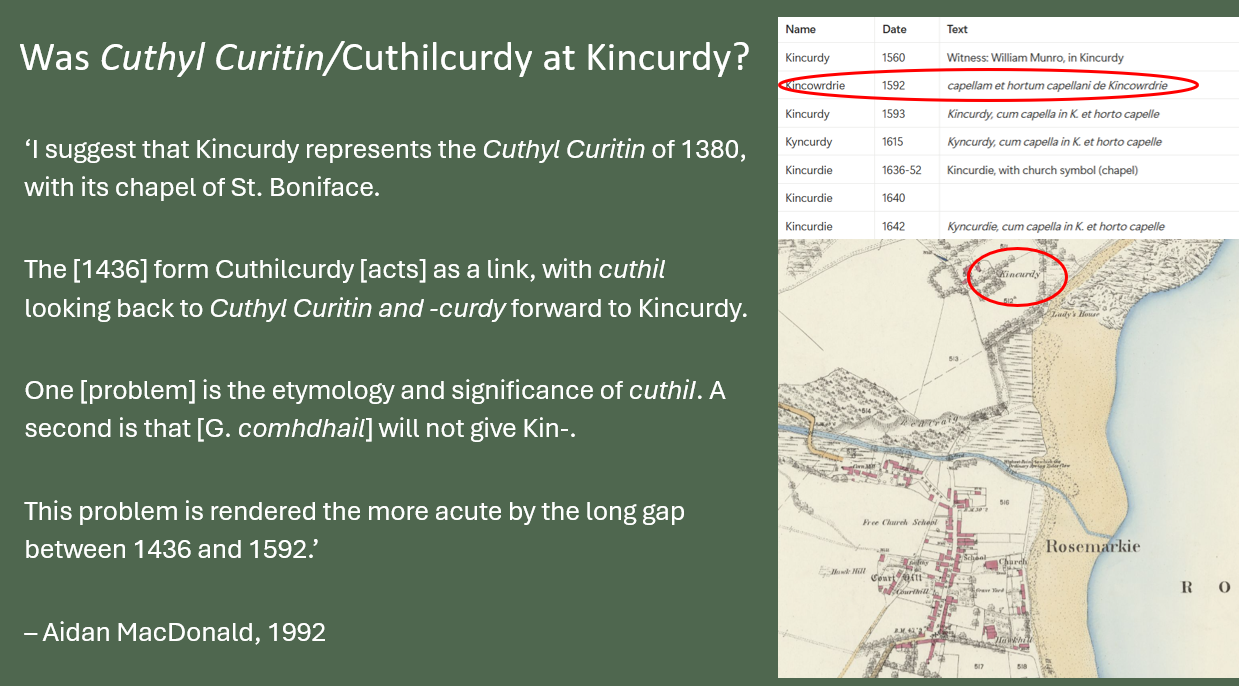

MacDonald proposed that Cuthyl Curitin, which does seem to contain Curetán’s name, is Kincurdy. He noted that Kincurdy is on record as having a chapel in 1592, and that the name Cuthyl Curitin had become the similar-sounding Cuthilcurdy by 1436.

He does acknowledge a couple of problems. Cuthyl—which he notes may be Gaelic comhdhail, for ‘assembly place’—can’t become Kin. There’s also a long gap between 1436, when we see Cuthilcurdy, and 1592, when we have the first mention of a chapel at Kincurdy.

But still, the common ‘curdy’ element does at first seem quite persuasive.

After a lot of digging, though, I'd like to make a different proposal.

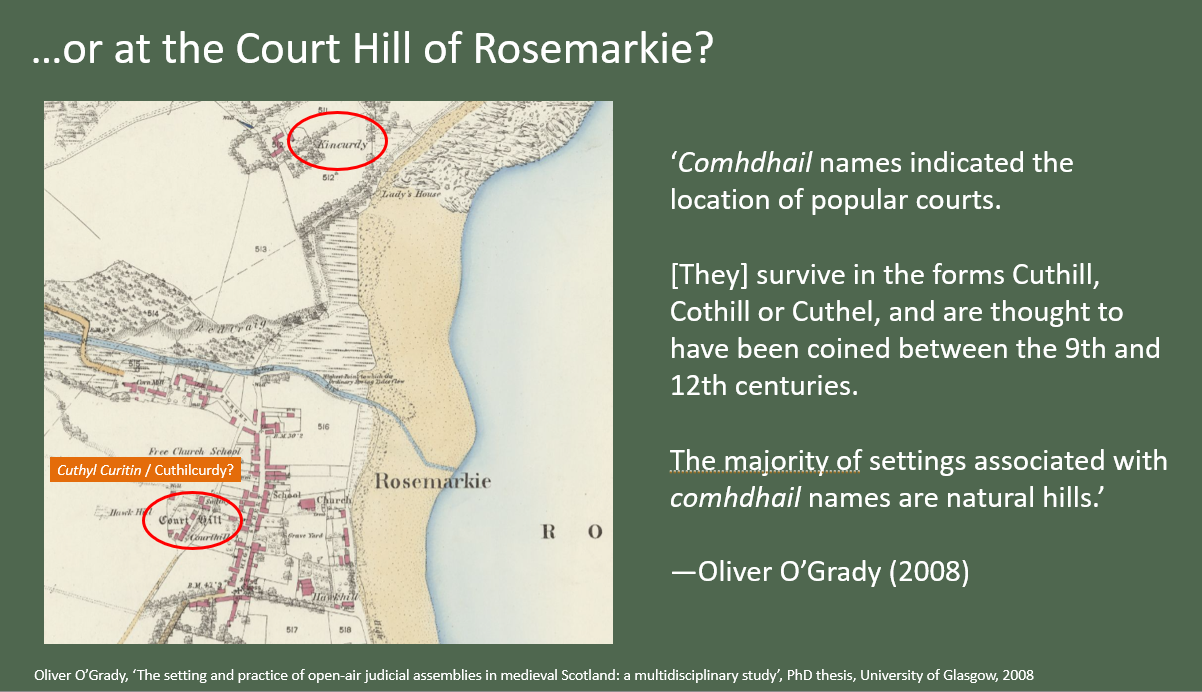

Was Cuthilcurdy the Court Hill of Rosemarkie?

Both Geoffrey Barrow in 1992 and the late Olly O’Grady in 2008 noted that comhdhail has a secondary meaning of ‘outdoor court site’. And in Rosemarkie village there is a ‘Court Hill’, mentioned in both the Old and New Statistical Accounts.

Curetán, as a bishop, almost certainly had judicial responsibilities, of the type set out in the eighth-century Collectio Canonum Hibernensis. So it’s possible that an outdoor court site adjacent to his see might have been used by him and preserved his name.

The 1380 charter suggests that there was a chapel at Cuthyl Curitin dedicated to St Boniface, who we know was Curetán.

There’s a tiny bit of support for this, in that a fragment of a probably ninth-century cross-slab (below) was reportedly found in a garden at Court Hill in the 1970s.

It’s just possible that an early medieval chapel initially dedicated to Curetán, who was rebranded as Boniface in the 12th century, survived at the Court Hill into the 14th century.

I’ve also managed to trace a bit more of the history of the chaplainry endowed in 1380 by Walter and Euphemia Leslie.

In 1436, as MacDonald noted, it was named the chaplaincy of Cuthilcurdy. But in 1574 it’s named in the Register of the Privy Seal as the chaplainry of Drimmen—that is, Drummond—but still situated in the chapel of St Boniface.

In 1963, the Fortrose historian Charles George MacDowall made a very plausible suggestion for the location of this chapel in 1574—and it wasn’t at Rosemarkie or Kincurdie.

He noted that the bishopric of Ross moved from Rosemarkie to Fortrose in the 13th century, but that the new cathedral wasn’t completed until sometime after 1394.

He proposed that once the cathedral was complete, the chapel of St Boniface moved there from Rosemarkie, leaving behind its old names of Cuthyl Curitin and Cuthilcurdy.

If this is correct—and given that the cathedral was dedicated to St Boniface, I think it is—then the chapel recorded at Kincurdy in 1592 and onwards is not the chapel of Cuthilcurdy.

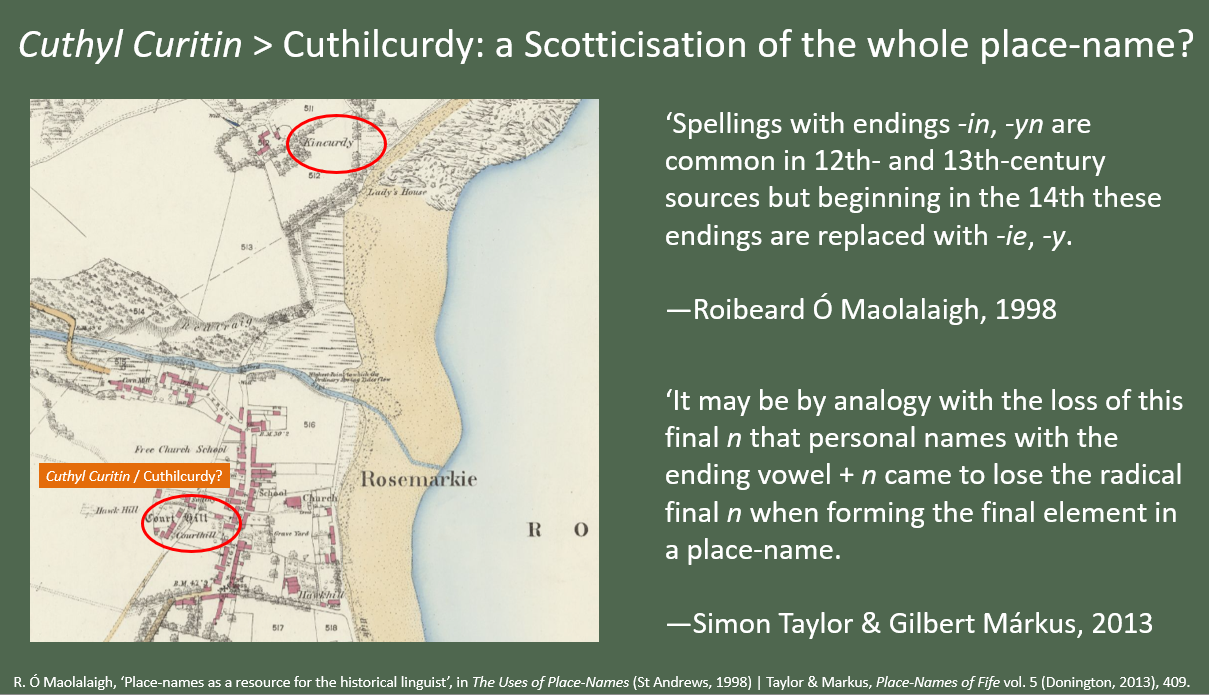

No familiar form 'Curdie' in Cuthilcurdy?

And given that all of the other evidence for a Scots familiar form ‘Curdie’ for Curetán has melted away, we can legitimately question whether this is really what we see in the name Cuthilcurdy.

I’d actually suggest that it’s the whole Gaelic name Cuthyl Curitin that’s been Scotticised as Cuthilcurdy, with the Gaelic ending -in going to Scots -ie as discussed by Robert O’Maolalaigh, Simon Taylor and Gilbert Márkus. It may even have been influenced by the existence of Kincurdy nearby.

Far from Curetán being remembered in this name, then, I’d propose that this change in ending is actually another sign that, locally in the Black Isle and Easter Ross, he had been thoroughly forgotten.

In summary...

So just to sum up. In 1992 Aidan MacDonald proposed that a familiar Scots form of Curetán, 'Curdie', lay behind three Black Isle place-names: Hill o’Hirdie, Kincurdy, and Cuthilcurdy.

But digging into each name has shown that this is almost certainly not the case.

In the case of Hill of Hirdie, it was a whimsical 19th-century Gaelicisation of the name as Cnoc gille-churdaidh that led in 1900 to an association with Curetán.

In the case of Kincurdy, the topography and the lack of a strong connection to Curetán suggest that the name is a possibly-Pictish ‘place at the end of a tapering point’’.

Only the name Cuthilcurdy demonstrably contains Curetán’s name, in its older, 14th-century form Cuthyl Curitin. But rather than representing a Scots familiar form, its -curdy ending is more likely to be a sign that Curetán’s name no longer held any meaning in the 15th-century Black Isle.

Overall, I have to conclude that a cult of our eighth-century bishop Curetán did not survive into the Scots-speaking later Middle Ages. Instead, it died out sometime before 1195, giving way to the cult of Boniface—whose fair is still held annually in the Black Isle today.

Thank you very much for listening (and now reading!)