In search of Adomnán’s 'stagnum Lochdae'

In which I propose a location in northern Pictland for a body of water that Adomnán, in his Life of St Columba, called stagnum Lochdae, or Loch Lochdae.

With many thanks to those who contributed valuable insights, information and expertise to this blog: Christopher Campbell-Howes, Alan G. James, Jake King, Iain MacIllechiar, Robaidh MacilleDhuibh, Roddie MacLennan and Gilbert Márkus.

For this blog I want to think about the location of a body of water that Adomnán, in his Life of St Columba, called stagnum Lochdae, or Loch Lochdae.

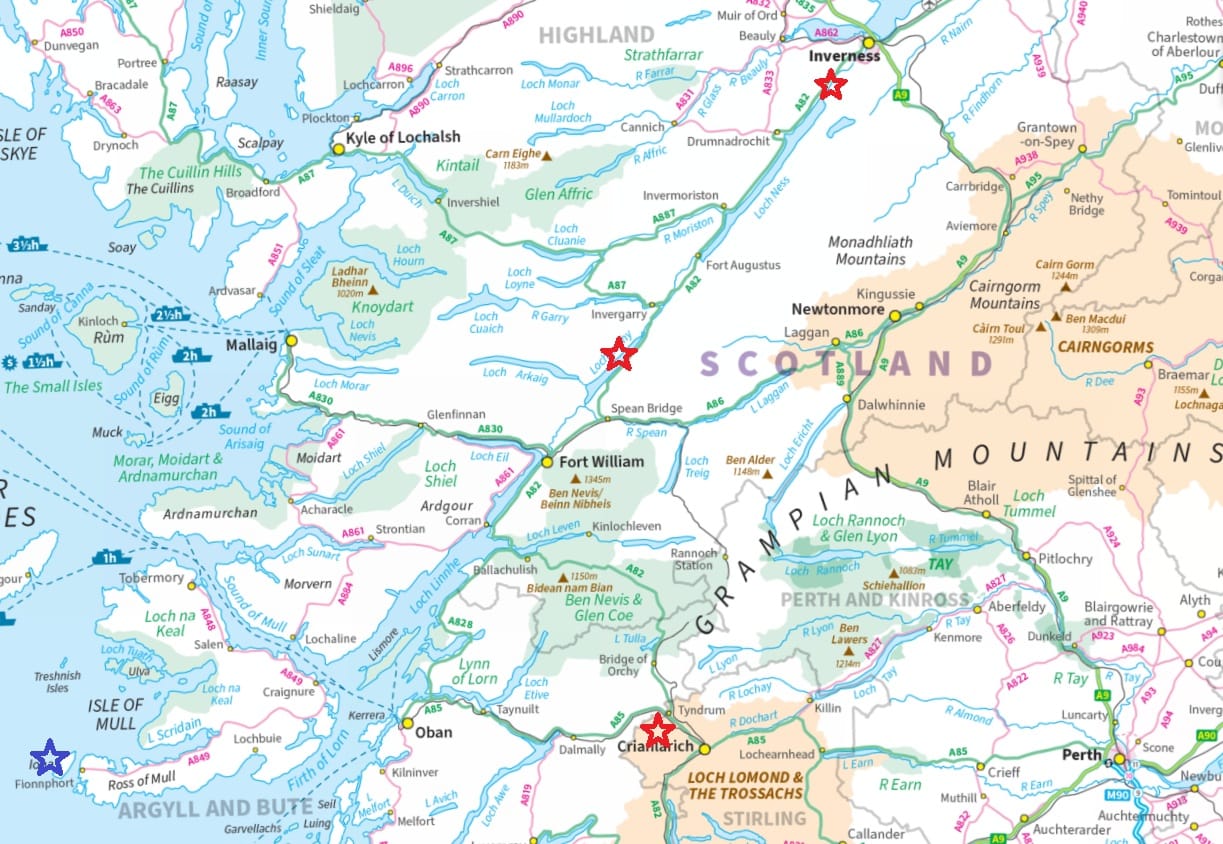

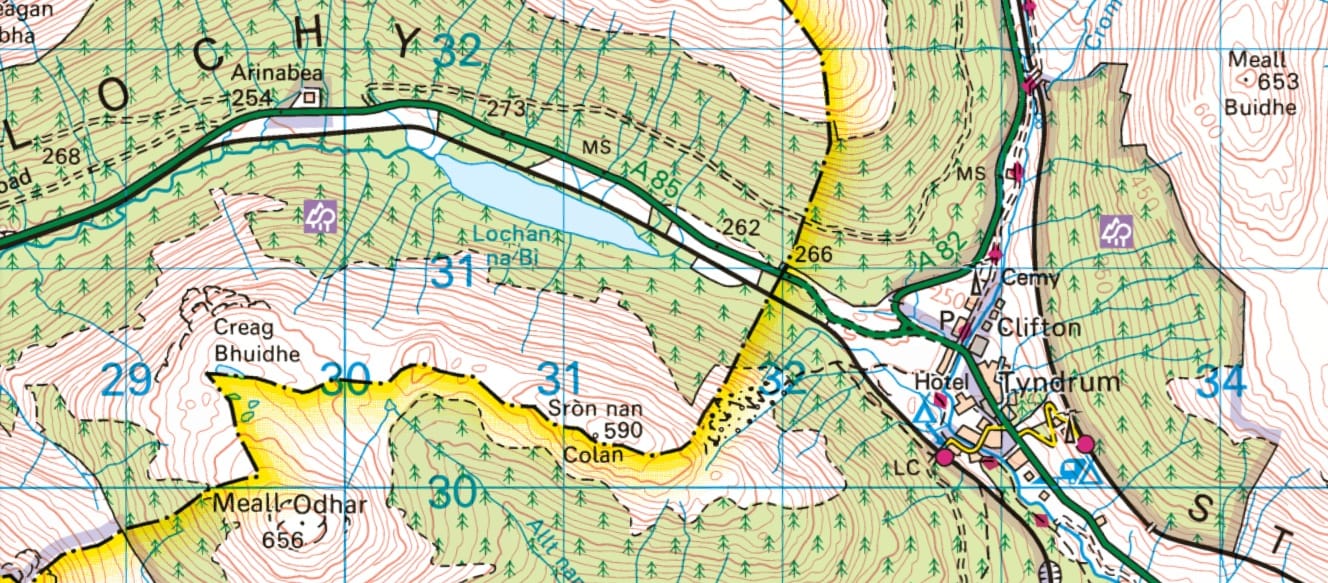

It’s usually identified as Loch Lochy in the Great Glen, between Loch Linnhe and Loch Oich. The other main candidate is the tiny but geopolitically-significant Lochan na Bì, on the border of Argyll and Perthshire just west of Tyndrum.

But there are good reasons to doubt both of these locations, and in this blog I want to suggest a third option: the body of water now called Loch Dochfour, between Loch Ness and the River Ness. As we’ll see, it much better fits the context of Adomnán’s narrative, and there is some slight evidence that it did once have a name like ‘Lochy’.

Adomnán and the sources for the Life of St Columba

As I’m going to propose that stagnum Lochdae was in northern Pictland, I need to outline the current academic thinking about Adomnán’s treatment of Picts and Pictland in his Life of St Columba (hereafter VSC for Vita Sancti Columbae).

Adomnán (d. 704), the ninth abbot of Iona, wrote VSC in the years leading up to 700. It’s not a biography as we would understand it, and it certainly shouldn’t be treated as one. Instead, it’s a collection of stories about miracles and wonders worked by the adult Columba (d. 597), both in his lifetime and occasionally posthumously.

Adomnán drew on two main sources: firstly, stories told about Columba passed down from those who had known him, and secondly – and crucially for this blog – from an earlier and now-lost Life of the saint written c. 640 by the seventh abbot of Iona, Cumméne Ailbe (d. 669).

There’s strong evidence that Adomnán copied significant portions of VSC from Cumméne’s text, making tweaks and edits to bring it into line with what he wanted to communicate. Academics including Máire Herbert and James Fraser have analysed VSC in depth to establish which parts were copied from Cumméne, and which were Adomnán’s own original work.

Distinguishing Cumméne’s work from Adomnán’s

In her 1988 book Iona, Kells and Derry, Professor Herbert argued that the biggest ‘tell’ is that Cumméne’s stories show Columba performing quite mundane miracles, while the miracles described by Adomnán are spectacular. Cumméne, for example, has Columba predict that a visitor to Iona would knock over his inkwell, whereas Adomnán has Columba vanquishing a monster and raising a boy from the dead.

In a 2003 article titled ‘Adomnán, Cumméne Ailbe, and the Picts’, Dr Fraser added three very interesting points. First, while Cumméne and Adomnán both show Columba travelling in Pictland, Cumméne’s stories are vague about the places the saint is visiting, but Adomnán cites specific place-names and describes the landscape in greater detail.

Second, Cumméne’s stories describe Pictland as lying ultra dorsum Britanniae or trans dorsum Britanniae – beyond or across the ‘spine of Britain’. (We’ll look shortly at what that term actually meant.) Adomnán, on the other hand, describes the action as happening in the provincia Pictorum or regione Pictorum – the province or region of the Picts.

Third, Fraser noted that Cumméne doesn’t mention the Picts by that name, or display any particular attitude towards them. Adomnán, however, uses the word ‘Picts’ and feels strongly about them. The ‘puffed-up’ Pictish king Bridei and his magus Broichan provoke animosity, for example, but the good pagan Emchath and his son Virolec are looked upon very benevolently.

So when it comes to Columba’s activity in Pictland, mundane miracles set vaguely ‘beyond the spine of Britain’ and with no particular feelings towards the locals are thought to come from Cumméne’s work, while spectacular miracles set in named places in the ‘province of the Picts’, and with strong feelings about Pictish people, are thought to be from Adomnán’s own pen.

However, it’s not always that cut and dried. Fraser argued that Adomnán co-opted some of Cumméne’s stories for his own purposes, changing details and adding his own flourishes. One is the story involving Emchath and Virolec that Adomnán chose to set at Airchartdan (Urquhart on Loch Ness). Another, as we’ll see, is the story set on the shores of stagnum Lochdae.

Adomnán’s ‘tripartite mental map’ of north Britain

Also relevant to this topic is Gilbert Márkus’s very interesting analysis of what he called Adomnán’s ‘tripartite mental map’ of north Britain, which I discussed in this blog.

In 1999, Márkus convincingly argued that Adomnán presents Iona as a safe, holy place, and the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata as a benign, Christian land. But when it comes to Pictland, he shows us a ‘wild and oppositional’ place, an ‘un-Christian’ territory full of dangers and threats.

In my blog I argued that there’s a little more nuance to Adomnán’s view of Pictland, especially to the seven episodes set in the Inverness area. The wild, threatening things only seem to happen around the River Ness – including Columba’s encounter with the murderous River Ness Monster. Loch Ness, by contrast, is a place of angelic visions, noble pagans, and gentle breezes.

This contrast is worth keeping in mind, as it’s into this Ness-side landscape that I’d like to insert the episode set at stagnum Lochdae. With that, we’d better have a look at what it actually says.

The boat that was moved in the night

VSC isn’t arranged chronologically, but is rather grouped under three themes: prophecies, miracles and angelic visions. Book I focuses on prophecies, and it recounts occasions when Columba foresaw or foretold some event. Chapter 34 is the one I’m interested in. In Alan and Marjorie Anderson’s 1961 translation, it’s titled:

Concerning a boat transferred from one place to another by night, at the command of the saint

It sets the scene thus:

At another time, the saint, on a journey across the spine of Britain, finding a hamlet among deserted fields, made his lodging there beside the bank of a stream that flowed into a lake.

Then the action starts:

In the same night, when his companions were slumbering, and had tasted their first sleep, he roused them, saying: 'Go out now, go quickly, and bring hither at once our boat that you left in a house beyond the stream; and place it in a nearer hut.' They obeyed at once, and did as they were bidden.

Next we discover how this qualifies as a miracle of prophecy:

And when they were again at rest, after some little time the saint silently touched [his servant] Diormit, saying: 'Now stand outside the house, and see what is happening in the hamlet where first you put your boat.' Obeying the saint's command, he left the house, looked back, and saw that the whole village was being consumed with devastating flame.

And finally the dénouement:

He returned to the saint, and reported what was happening there. Thereupon the saint gave the brothers an account of a certain hostile pursuer who had set fire to those houses on that night.

James Fraser noted that this short chapter has several hallmarks of a Cumméne story. The action takes place ‘across the spine of Britain’, the Picts aren’t named, Columba’s powers of foresight are fairly low-key, there’s no dramatic confrontation or spectacular miracle, and no place-names are mentioned.

But we also see touches of what Herbert and Fraser identified as Adomnán’s personal style. The landscape is described in detail: ‘a hamlet among deserted fields… beside the bank of a stream that flowed into a lake’. The territory seems dangerous, with a ‘hostile pursuer’ intent on destruction – although it’s unclear whether Columba and his companions are the target.

And, crucially, in Adomnán’s table of contents, but not in the chapter itself, the place where this episode unfolds is given a specific name:

De nauiculae transmotatione iuxta stagnum Lochdae.

Of the removal of a boat, beside the lake of Lóchdae.

A location in north or south Pictland?

James Fraser had an interesting view on why this loch-name only appears in the table of contents. He argued that Adomnán had removed the location from the chapter (but forgot to remove it from the table of contents) because he felt political pressure from Pictland to show Columba working only among the northern Picts.

Fraser surmised that Cumméne, writing in 640, had shown Columba in southern Pictland – perhaps in or on the way to Tayside, where an early Iona poem, Amra Choluimb Chille, says he converted a ‘great king’ and his subjects. But by 700 when Adomnán was writing, the view of the Pictish political class was that Columba had worked among the northern Picts only. According to Fraser, Adomnán therefore removed any information that would place Columba in the south.

If Fraser’s suspicion was correct, it would imply that stagnum Lochdae was somewhere in southern Pictland, either within or south of the massif known as the Grampians or the Mounth. And there’s a bit of support for this in that a very similar loch-name, stagnum Loogdae, is mentioned in the Annals of Ulster for the year 729. It says (with Alex Woolf’s 2006 translation from this article):

Bellum Monith Carno iuxta Stagnum Loogdae inter hostem Nectain 7 excercitum Oengusa

The battle of Monith Carno by Loch Loogde between the enemy of Nechtan and the army of Oengus

In his 1926 book The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, the place-name scholar W. J. Watson identified stagnum Loogdae as the tiny Lochan na Bì (NN 3089 3127), just on the Argyll side of the Argyll-Perthshire border. This loch is the source of one of several Scottish rivers called Lochy, which flows westwards until it joins the River Orchy at Inverlochy (NN 1964 2754). In that sense, it’s the loch (stagnum) of the River Lochy (Loogdae).

Watson’s reason for placing stagnum Loogdae here was that the battle of Monid Carno seems to have been part of an ongoing power struggle between rival claimants for the kingship of the Picts. The previous battle, recorded in the annals for 728, was fought at a place called Monidh Croibh, which Watson and others have identified as Moncreiffe Hill (NO 13813 19713) just south of Perth. In Watson’s view, this made a Perthshire location likely for stagnum Loogdae.

However, Watson didn’t think that the stagnum Lochdae of VSC and the stagnum Loogdae of the Annals of Ulster were the same loch, even though they had the same name. He noted that there are multiple bodies of water and watercourses in Scotland with the name Lochy or Lochty, and he was inclined to identify Adomnán’s stagnum Lochdae with Loch Lochy, presumably because Adomnán had set seven other stories in the Great Glen.

The current front-runners: Lochan na Bì and Loch Lochy

These two lochs – Lochan na Bì and Loch Lochy – have become the front-runners for the location of stagnum Lochdae, and scholars have tended to favour one or the other depending on the thrust of their argument.

For Fraser, Lochan na Bì was the preferred option because his argument was based on the idea that Cumméne had portrayed Columba at work in south Pictland, and Adomnán had relocated him to the north. Another scholar who considered Lochan na Bì for stagnum Lochdae is Philip Dunshea, who wrote an excellent article in 2013 on what Adomnán meant by the term dorsum Britanniae, or ‘spine of Britain’, across which Columba and his companions were journeying.

Dunshea noted that the prevailing view is that dorsum Britanniae referred to a mountain range that separated Dál Riata from Pictland. But this isn’t a very satisfactory interpretation, as neither the Moray Firthlands nor Atholl can be described as lying ‘beyond’ or ‘across’ a mountain range from Argyll. The Firthlands are reached via the Great Glen, not crossing any mountains, and Atholl lies within a single mountainous massif that stretches across both Dál Riata and Pictland.

Dunshea sided instead with the nineteenth-century historian William Forbes Skene, who had identified dorsum Britanniae as the Atlantic-North Sea watershed. This feature is a much better fit for the metaphor of a dorsal ridge or spine, from which rivers flow on either side. The line of the watershed also aligns pretty well, at least in parts, with our understanding (from place-names, sculpture and texts) of which areas of Scotland lay in Dál Riata and which in Pictland.

Dunshea observed that a journey from Iona to Atholl would cross the watershed at modern-day Tyndrum on what is still the Argyll-Perthshire border. Indeed, as he noted, Tyndrum (Gaelic Tigh an Droma, ‘house of the ridge’) and a nearby feature called Carn Droma both contain the Gaelic word druim for ‘ridge’ or ‘spine’.

This, together with James Fraser’s argument, encouraged Dunshea to see Lochan na Bì, just west of Tyndrum, as the preferable candidate for stagnum Lochdae:

We have already seen how [VSC’s] focus on the Great Glen may at least partially be the result of later reworking… If the majority of [Cumméne’s] stories are released from this geographical framework, new possibilities become apparent. And if Columba had ever gone east to the Tay in pursuit of its ‘great king’, he might well have passed along Glen Lochy and thence to Loch Tay. Lochan na Bi, although small, lay on an important route.

So there are good reasons to consider Lochan na Bì as the stagnum Lochdae where Columba and his companions nearly had their boat burned by a ‘hostile pursuer’.

The case against Lochan na Bì

But there are also serious problems with this identification. The main one, as Dunshea himself acknowledged (but Fraser did not), is that it is hardly believable that Columba would have taken a boat on the route through Glen Lochy, then via Strath Fillan and Glen Dochart, to Loch Tay.

This is a land route for most of its course, and is still followed today by the A85 road from Oban to Perth. Because of this, Dunshea ended up dismissing his own identification, concluding that:

Loch Awe to Loch Tay would have been an exceptional portage, even with a small coracle; Lochan na Bi is worth fishing on but probably not much more. If only for this reason, Loch Lochy in the Great Glen remains the preferable option.

Another reason to doubt Lochan na Bì as the location is that the episode takes place while Columba is ‘on a journey across the spine of Britain’ (trans Britanniam dorsum iter agens). While grammatically this could mean that Columba was heading towards Pictland, the fact that he and his companions encounter danger and hostility is a strong sign that the action takes place in Pictland itself. Lochan na Bì is (just) on the Dál Riata side of the watershed, making it a less certain candidate for stagnum Lochdae.

The case against Loch Lochy

This objection also holds true, however, for the other main candidate, Loch Lochy. The Atlantic-North Sea watershed runs between Loch Lochy and Loch Oich, with Loch Lochy on the Dál Riata side of the divide. Dunshea acknowledged this, noting that Loch Lochy is on the way to Pictland, rather than in Pictland proper:

Loch Lochy, towards the south-western end of the Great Glen, is the obvious candidate because it lies en route to the location of the [spectacular] miracles’.

And later, having dismissed his identification of Lochan na Bì, he noted:

Loch Lochy in the Great Glen remains the preferable option and we must accept that this location fits rather awkwardly with the description ‘trans dorsum Britanniae’.

The identification is awkward because we expect a location in Pictland for hostile events taking place ‘across the spine of Britain’. Neither Lochan na Bì nor Loch Lochy comfortably fits that bill.

But there is another possible candidate – and one that fits very well with the other stories in which Adomnán shows Columba in Pictland. It hasn’t been considered before, but I think it has quite a few things going for it.

The case for Loch Dochfour

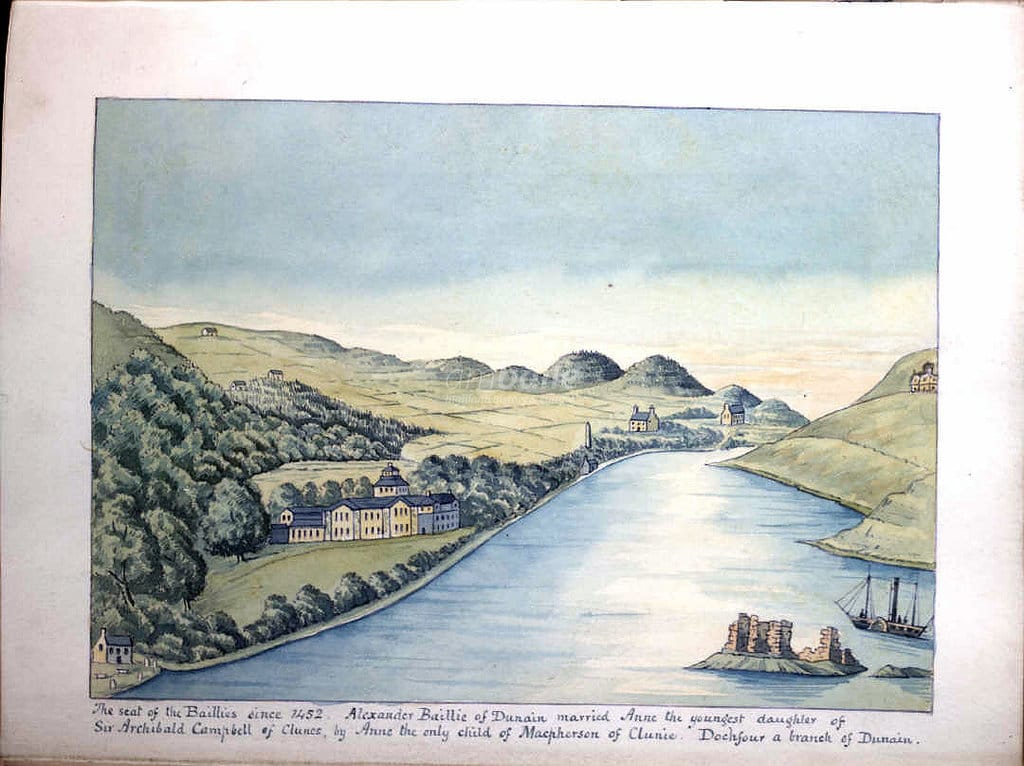

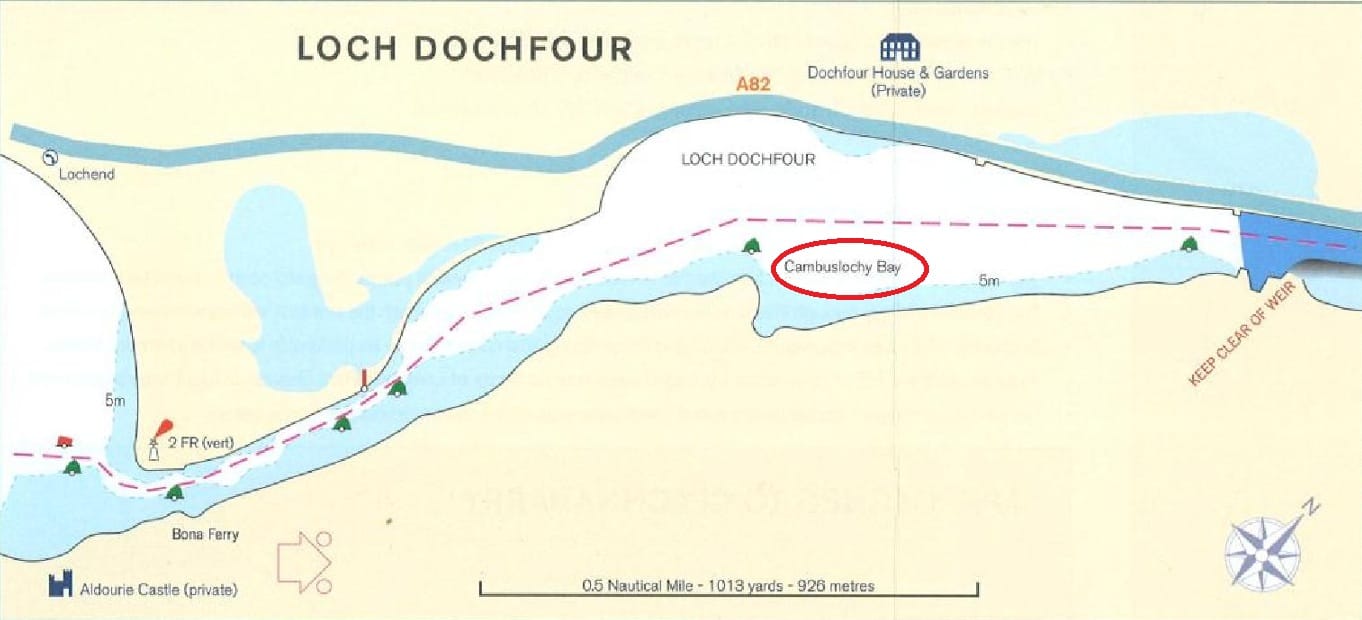

The candidate I have in mind is the body of water called Loch Dochfour, which lies between Loch Ness and the River Ness. It’s named after the house and estate of Dochfour on its western flank, which has been the seat of a branch of the Baillie family since the fifteenth century.

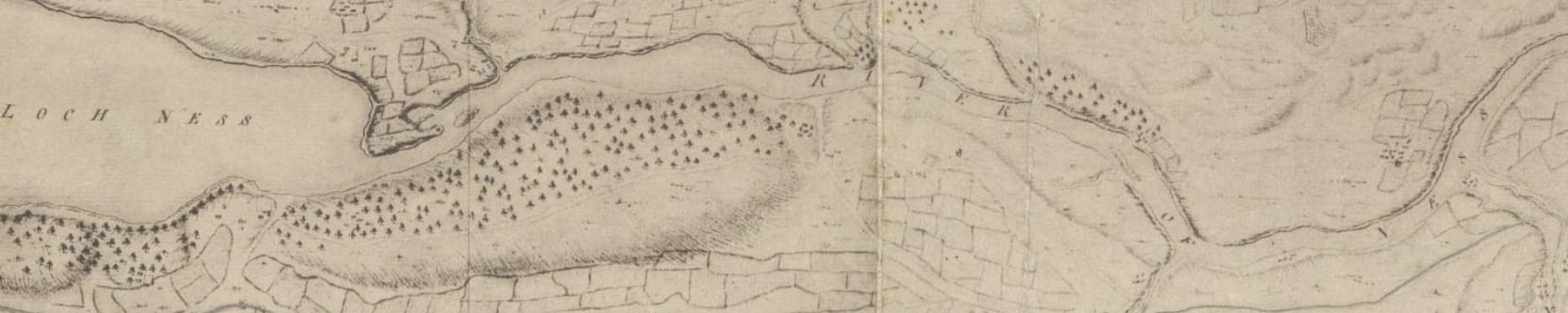

However, the loch only acquired this name relatively recently. A map of 1792 by George Brown – many thanks to Robaidh MacilleDhuibh for sharing it with me – shows it as ‘Little Loch’ (below), while an anonymous 1725 map of the area around the foot of Loch Ness gives it no specific name.

In a discussion on the Scottish Place-Names Facebook Group, Roddie MacLennan made the very good point that Loch Dochfour as it exists today is a product of the Caledonian Canal engineering works of 1817, which deepened a channel along its length.

Prior to this, the loch would have been shallower and perhaps not as wide – although pre-1817 maps are inconsistent on its width and outline. A shallow loch is certainly what’s suggested by the earliest instance of the name ‘Loch Dochfour’ that I’ve been able to find. A letter to the Aberdeen Press & Journal of 1809 states that:

The frost has been more intense… than we ever remember. The river Ness… is now frozen for several yards, in places where the water happens to be shallow and motionless. Indeed, Loch Dochfour, which may be considered a continuation of Loch Ness, but of no great depth, is… nearly frozen over.

This letter gives us a glimpse of the loch before the canal works began in the area, and provides an insight into what distinguished it from Loch Ness to its west and the River Ness to its east. Unlike Loch Ness, it was shallow, and unlike the River Ness, it was still.

These qualities may have marked it out as a discrete body of water in Adomnán’s time, when it lay on the major routeway between Dál Riata and northern Pictland, and may have earned it a separate name at that period too.

The toponymic evidence: Cambuslochy Bay

But is there any evidence that the early medieval Loch Dochfour had a name like Lochy or Lochty, the two Gaelic name-forms suggested by stagnum Lochdae?

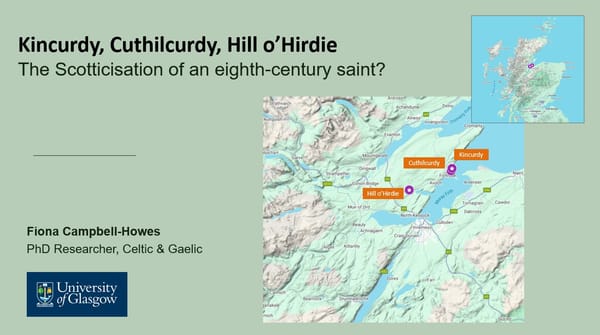

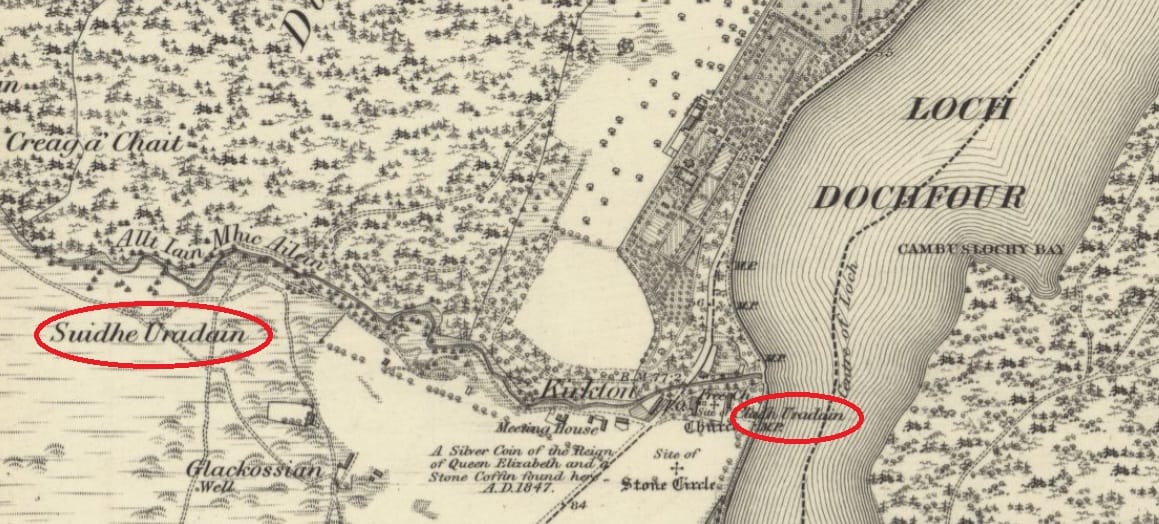

Well, tantalisingly, there is. On the first-edition OS maps of Loch Dochfour (below), a pronounced inlet on its eastern flank is given the name ‘Cambuslochy Bay’. This name no longer appears on OS maps, but it can still be found on navigational charts of the Caledonian Canal.

This was the name provided to the Ordnance Survey in April 1871 by three local informants in Dores parish: Mr D. Whyte of Cullaird, Mr D. Kennedy of Dores, and William Webster of Antfield. The surveyor duly recorded it in the OS Name Book for Dores parish as follows:

Cambuslochy Bay: This name is applied to a small bay, situated on the east side of Loch Dochfour, about ½ a mile north of Bona Ferry.

Cambuslochy Bay can’t be its original name, however. It must be an anglicisation of a Gaelic name, since the fact that it’s a bay is already conveyed in the element ‘cambus’, which is Gaelic camas, ‘bay’.

Indeed, in 1902, W. J. Watson noted the bay’s Gaelic name as Camas-lòchaidh, citing one Hugh MacLennan, who had also advised him on other Gaelic hydronyms in the Inverness area. He translated this name into English as ‘Lochy Bay’, but that is a bit of a cop-out. Camas certainly means ‘bay’, but Watson’s translation doesn’t shed any light on what we should infer from lòchaidh in this particular name, and no other toponymist has dug into the name either.

But in 2005, in a detailed analysis of other ‘Lochy’ names in Scotland, Jake King noted that lòchaidh with a long ‘o’ contains the Old Irish adjective lóch, meaning ‘shining’, and not, as one might expect, the Scottish Gaelic noun loch for ‘lake’, or indeed the Old Irish adjective loch, meaning ‘black’. He also noted that the adjective lóch for ‘shining’ is obsolete in Scottish Gaelic, suggesting that camas-lòchaidh, or at least the lòchaidh element of it, is a very old name.

He went further, proposing that lòchaidh names found in areas that were in Pictland, like Cambuslochy Bay, were originally Pictish names that were later Gaelicised. Since Pictish was a P-Celtic language akin to Welsh, this would mean that the lòchaidh of camas-lòchaidh was originally something like Welsh llugdde, for ‘shining, brilliant’. This would be consistent with Adomnán’s spelling Lochdae, and would also explain why lòchaidh hydronyms don’t occur in Ireland.

So despite the fact that it’s not on record until 1871 (although I haven’t dug properly into the archives to look for older instances), ‘Cambuslochy Bay’ has a good chance of preserving a name that has survived from Pictish times, first in a gaelicised and then in an anglicised form.

A relic of a Pictish name for Loch Dochfour?

Another observation made by King was that in Pictland, lòch names apply uniquely to rivers and flowing watercourses. This led him to discount Camas-lòchaidh from his discussion:

Lochy Bay has not been included in the main discussion, since it is only found in Watson and it is not a watercourse, although its location is consistent with the distribution of Lochy names.

But this may be doing Camas-lòchaidh a bit of a disservice. As we’ve seen, it’s not only found in Watson, but is also present in anglicised form in Cambuslochy Bay. And while the bay itself is not a watercourse, the wider Loch Dochfour arguably is part of the River Ness.

On this point, other lòch names considered by King are not watercourses either: he cited Poll-lòchaig and Innis-lòicheil, both also in Inverness-shire, and translatable respectively as ‘Lochy Pool’ and ‘Lochy Water-Meadow’. The implication – as I understand it, at least – is that these names were secondary names that persisted after the watercourse they belonged to ceased to be called ‘Lochy’.

In which case, we could apply the same thinking to Camas-lòchaidh: that it was once a feature of a watercourse called Lòchaidh – or more properly something like *Lugdde – whose name was subsequently changed to something else, leaving the original name attached only to the bay.

Since we’ve seen that Loch Dochfour only acquired that name around the turn of the nineteenth century, and that it was previously known in English as ‘Little Loch’, a name which cannot be ancient, it is at least possible that around the turn of the eighth century it was known by a Pictish name *Lugdde, meaning ‘shining, brilliant’, and which was rendered Lochdae by the Gaelic-speaking Adomnán.

Loch Dochfour fits very well with Adomnán’s narrative

If I’ve managed to persuade you that this is an idea worth entertaining, then I want to finish by looking at exactly what Adomnán says about stagnum Lochdae. Because if we imagine that he is talking about Loch Dochfour, I think we can see something quite remarkable.

First, we see the quite specific topographical detail that Columba, ‘finding a hamlet among deserted fields, made his lodging there beside the bank of a stream that flowed into a lake’.

Adomnán then insinuates that Columba’s party had left their boat on the far side of this stream, where it was nearly destroyed in the night by a ‘hostile pursuer’. It was only saved by bringing it in the nick of time round to their side of the stream.

The only stream of any size that flows into Loch Dochfour is the one now called the Lochend Burn, which enters the loch at Kirkton on its west bank. As I noted earlier, elsewhere in VSC Columba encounters danger and hostility only around the River Ness. Loch Ness, by contrast, was a welcoming space for him. It would make narrative sense, then, that a ‘hostile pursuer’ would approach from the direction of the river, and that the ‘safe’ side of the stream was the one closer to Loch Ness.

And what do we find right next to the Lochend Burn on its Loch Ness side? A church site, indeed the old parish church of Bona. But it's not just any church site: it's one that is heavily dedicated to Curetán, who was bishop of Ross at the exact time that Adomnán was writing VSC, and who was personally known to Adomnán, since he was a supporter, in 697, of Adomnán’s Law of the Innocents.

Notably, all three Curetán dedications lie on the Loch Ness side of the stream. The kirkyard is called Cladh Uradain, Curetán’s burial ground, and above the church are Suidhe Uradain, Curetan’s Seat, and Ruigh Uradain, Curetán’s slope.

I’ve spoken elsewhere about how the very compact cluster of Curetán dedications in the Firthlands have all of the hallmarks of being very early in date; even contemporaneous with the saint’s actual activity. To me, it’s not a stretch to imagine that a church existed on this same spot in Adomnán’s time, under the purview of his associate, bishop Curetán.

All scholars of Adomnán also agree that he had his own motives for composing VSC when he did, and in the way he did. To present a church at Bona as a safe haven in an otherwise hostile part of Pictland may well have had contemporary resonances for Adomnán, Curetán and the Columban community which are lost to us now.

Conclusion: A more fitting location for stagnum Lochdae?

In this blog I’ve offered another option for the location of the stagnum Lochdae where Adomnán sets one of the chapters of VSC that portray Columba in Pictland, trans dorsum Britanniae.

I’ve shown that both of the previously-proposed locations, Lochan na Bì and Loch Lochy, are problematic, particularly (but not only) because neither of them is unambiguously in Pictland.

Instead, based primarily on Watson’s identification of Cambuslochy Bay in Loch Dochfour as Gaelic Camas-lòchaidh with a long ‘o’ meaning ‘shining’, and Jake King’s analysis of lòchaidh names in eastern Scotland as having Pictish rather than Gaelic origins, I’ve proposed that the body of water now called Loch Dochfour is a candidate worth considering.

Not only does it (just about) pass the linguistic test, but it also fits extremely well both with Adomnán’s topographical description of stagnum Lochdae, and with the psychogeography of Loch Ness and the River Ness evident in all of the other chapters of VSC set in the Inverness area.

Loch Dochfour represents a frontier between the safety of Loch Ness, where Columba experiences a vision of angels and baptises a good pagan and his noble family, and the hostility of the River Ness, where he clashes with the puffed-up King Bridei and his arrogant magus Broichan, and defeats a terrifying river-beast that almost devours one of his monks.

The icing on the cake is that Adomnán narrows this frontier down to a single stream, identifiable in this scenario as the Lochend Burn that flows into Loch Dochfour at Kirkton of Bona, and on the ‘safe’ side of which we find an ancient church site dedicated to Adomnán’s associate, bishop Curetán.

I think this idea has quite a lot going for it, in other words – but I’d be very interested in any thoughts!

References

Anderson, A., and M. O. Anderson, Adomnán’s Life of Columba (London, 1961).

Dunshea, P., ‘Druim Alban, Dorsum Britanniae – “the Spine of Britain”’, Scottish Historical Review 92:2 (2013), 275–289.

Fraser, J. E., ‘Adomnán, Cumméne Ailbe and the Picts’, Peritia 17–18 (2003), 102–120.

Herbert, M., Iona, Kells and Derry: The History and Hagiography of the Monastic Familia of Columba (Oxford, 1988).

King, J., ‘”‘Lochy” Names and Adomnán’s Nigra Dea’, Nomina 29 (2005), 69–91.

Márkus, G., ‘Iona: monks, pastors and missionaries’, in Spes Scotorum, Hope of Scots: Saint Columba, Iona and Scotland, edited by Dauvit Broun and Thomas Owen Clancy (Edinburgh, 1999), 115–138.

Ordnance Survey Name Book, Dores parish, OS1/17/22, April 1871.

Watson, W. J., Scottish Place-Name Papers (London, 2002).

Watson, W. J., The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (London, 1926).

Woolf, A., ‘AU 729.2 and the last years of Nechtan mac Der-Ilei’, Scottish Historical Review 85:1 (2006), 131–137.