History: Once more, with feeling

I hated history at school – why am I so keen to study it now?

When I start my History MA this September, it’ll have been 34 years since I last studied history, at school, for A level.

I didn’t want to do History A level, but was encouraged to, not because I was good at it – it had been one of my worst O level subjects, on a par with maths – but because my preferred options didn’t work timetable-wise (French, German and Biology) or were seen as too “fluffy” (French, German and History of Art).

Once it got underway, History A level was even worse than I’d feared. On the European history side it was all Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini, and I can’t even remember which period we studied for British history, other than that it was modern and I hated it.

I ended up with a C, which, among other things, put to bed any dreams I’d had of re-applying to Oxford. (I’d applied the previous year, got rejected at the interview stage, and had planned to apply again if my grades were good enough. Thanks to History, they were not.)

I came to the conclusion that I just didn’t “get” history – that I didn’t have the intellectual capacity to discern grand themes, or understand political cause and effect, or get inside the psychology of the “Great Dictators” (who my history teachers alarmingly seemed to admire).

Maybe it was just the wrong kind of history

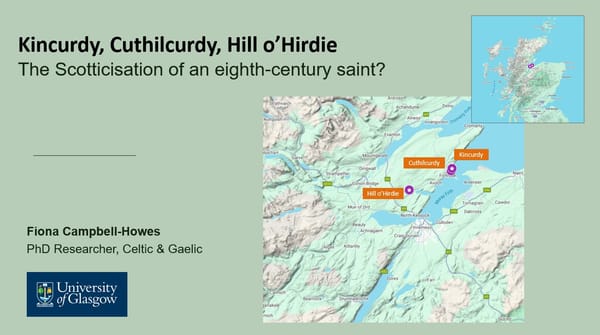

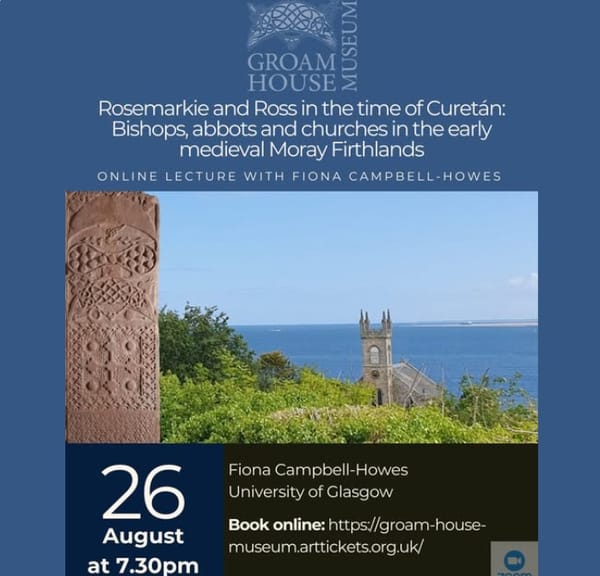

In reality, though, I think I just wasn’t interested enough in the period. Earlier this year I attended an online conference that included a talk by Professor Katherine Forsyth of the University of Glasgow, who talked about her route into Celtic studies.

Just as she was choosing her A levels, she said, her school decided to drop the Great Dictators and offer a History A level focused on early medieval Scotland instead.

She was the only student who chose it, and recalled how she was more or less left alone to work her way through a box of course materials, including (if I remember rightly) the legendary OS Map of Britain in the Dark Ages (North Sheet).

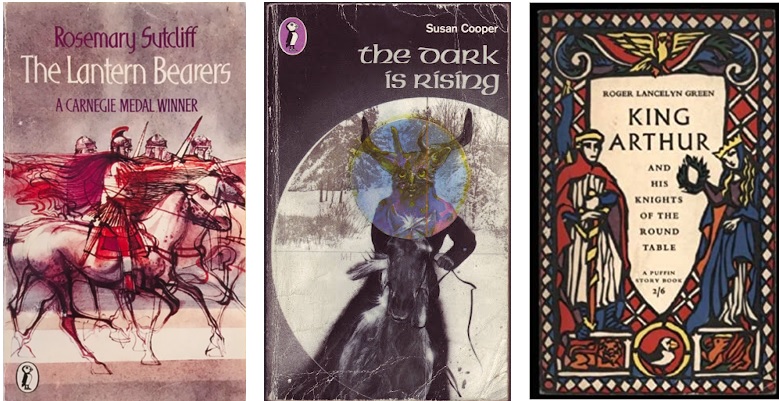

I listened to this with a huge pang of envy. How I would have loved History A level if it had meant being left to my own devices to study the early middle ages! I’d grown up reading books like Rosemary Sutcliff’s The Lantern Bearers, set in sixth-century Britain; Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising, with its Arthurian undertones; and Roger Lancelyn Green’s King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table.

Even among my pony books, my favourite was Patricia Leitch’s Night of the Red Horse – not for the horsey content, but because the plot revolved around an archaeological dig in the Highlands, and an artefact that harked back to a mysterious pre-Christian past.

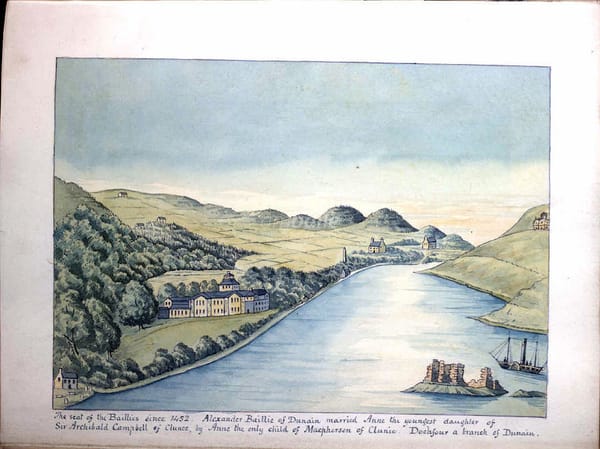

Archaeology was a perennial fascination. I drew Saxon churches from my parents’ Shell Treasury of the Countryside, and vaguely wondered why there weren’t any like that near where I lived. I was aware of the archaeological remains around me: the vitrified hillfort above our house, the ruined hall house on the far side of the burn, the huge carved pillar in Forres, said to commemorate a battle against the Vikings.

They seemed like gateways to another world: one, like Stranger Things’ Upside Down, that was both close and familiar and impossibly strange and far away. When I learned that some dwellers of this Upside Down had left hundreds of carved stones with unexplained symbols and indecipherable inscriptions, its lure only became stronger.

An attempt to reset the clock

If, like Katherine Forsyth, I’d had the opportunity to roll all of this juvenile fascination into a history A-level, things might have worked out very differently. Maybe I’d have gone to a Scottish university rather than an English one. Maybe I’d have chosen to study archaeology rather than languages. Maybe I wouldn’t have spent 25 years working in the tech industry. Who knows.

What I do know is that I’m now attempting to reset the clock – to roll back to my teens and choose a different, more rewarding life path. I have a photo of 17-year-old me stuck to the whiteboard above my desk, gazing up rather blankly from the breakfast table in Kinloss, circa 1987. I like to think she would be very excited about my imminent pivot from tech writer to historian of early medieval Scotland.

What’s my motivation here?

That said, I still think I don’t really “get” history and I worry I don’t have the right kind of brain or mindset for it.

My motivation isn’t to learn lessons from the past that can help us navigate the present, or to shed light on historic harms and injustices in a bid to start repairing them. And unlike many historians of early medieval Scotland, I don’t have a political axe to grind: although I would certainly vote for independence if I still lived there, I’m not interested in the origin story of a unified and independent Scotland.

On the other hand, I’m also not motivated by the kind of ethno-nationalism that pollutes Facebook groups and Twitter threads, with its endless references to a supposed ninth-century genocide of “indigenous” Picts by Irish “invaders” (for which there’s no reliable historical or archaeological evidence one way or the other).

Misguided evocations of a supposed age of ethnic purity lie at the root of some of the vilest modern-day thinking, and I’m glad that scientific advances are giving us much better insights into population mobility and cultural interplay in the first millennium.

No, what really motivates me is just a desire to “read” the landscapes of my childhood – to use texts, place-names and archaeology to try to extract more meaning from the vestiges of early medieval human activity that dot the southern shore of the Moray Firth. Whether I’ll be any good at it – or it will prove in any way useful for the wider world – remains to be seen!